Regenerative medicine is the branch of medicine that focuses on the regeneration of damaged organs and tissues. It includes cell-based therapies, grafting or implantation of cells, gene therapy, and treatments based on growth factors and stem cells. Regenerative medicine is mainly applied to the following wounds:

- Wounds with loss of substance or risk of infection

- Suture or stoma dehiscence

- Abscesses and fistulas.

According to Pang et al (2017), wounds can be classified as acute or chronic. Acute wounds are those caused by surgery or trauma, typically healing within three weeks (Tottoli et al, 2020). The exudate from acute wounds is rich in leukocytes and nutrients. However, the acute healing process is susceptible to disruption or failure due to multiple factors that may affect all stages of healing (Bielefeld et al, 2013).

Surgical wounds are acute skin injuries resulting from surgical procedures conducted under sterile conditions, which are then left to heal by primary intention. They typically appear flat and are expected to heal without complications. Studies (Landén et al, 2016; Takagi et al, 2016) have indicated that while the inflammatory phase is crucial for controlling microbes, an imbalance in the cellular responses could lead to delayed wound healing. Primary intention healing may be delayed in the presence of infectious risk factors, such as when a drainage system is inserted.

Chronic or hard-to-heal wounds are characterised by a prolonged inflammatory response, persistent infection and lack of response to stimuli (Attinger et al, 2006); their exudate contains high levels of proteases and proinflammatory cytokines.

When the skin edges cannot be joined without excessive tension or there is tissue loss, a secondary intention healing process is preferred. The traditional management of such surgical wounds involves frequent dressing changes and packing of the wound cavity (Chetter et al, 2019).

Surgical wound dehiscence is attributed to various risk factors including age, sex, emergency procedures, type of surgery, postoperative cough and infection (Rucinski et al, 2001; Ceydeli et al, 2005; Van Ramshorst et al, 2010; Sandy-Hodgetts et al, 2013).

Traditional wound treatments aim to mitigate these risk factors and allow the normal healing process to progress towards scar formation (Pang et al, 2017), while regenerative strategies seek to achieve complete tissue regeneration and restore functionality (Schiavon et al, 2016). One such regenerative therapy involves the application of platelet-rich plasma (PRP), which accelerates the transition of the healing process from chronic to acute and promotes regeneration in traumatic and surgical injuries.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP)

PRP is acquired through the centrifugation of whole blood, which separates other cells, resulting in a concentrated platelet solution in blood plasma. Platelet concentrates are categorised based on various parameters, including characteristics of the preparation kit, final volume, platelet concentration, preservation method, fibrin network architecture and preparation methods (Gibble et al, 1990; Harrison, 2018). PRP can further be classified as activated or nonactivated, with activation achieved by adding substances such as calcium chloride, calcium gluconate or thrombin to produce a fibrin gel. Administration of PRP can be done through injection or topical application (Etulian, 2018).

Platelets have a-granules that contain primary growth factors necessary for tissue regeneration. These include transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-B) 1, 2 and 3, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), endothelial growth factors (EGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF).

Regulation of blood products

In Italy, the ‘Decree of the Blood,’ issued on November 2, 2015, and updated on August 1, 2019, establishes regulations to ensure the quality and safety parameters of blood and its components (Han et al, 2012). This decree governs the collection, storage, traceability and distribution of human blood and its derivatives, with regional authorities responsible for monitoring compliance. The law also stipulates specific requirements for platelet concentrate, including platelet and leukocyte concentrations of 1x106/μl ± 20% and <1x106/μl, respectively.

At our institution, we distribute various blood components for topical use, including autologous serum eyedrops, amniopatch for prelabour rupture of membrane cases with amniotic fluid leakage, and platelet gel (PRP and activator).

Aim

PRP, derived from human blood, can be used in the treatment of chronic or hard-to-heal wounds. In this case series, we describe the application of PRP in addressing challenging wounds in seven paediatric patients.

Case results

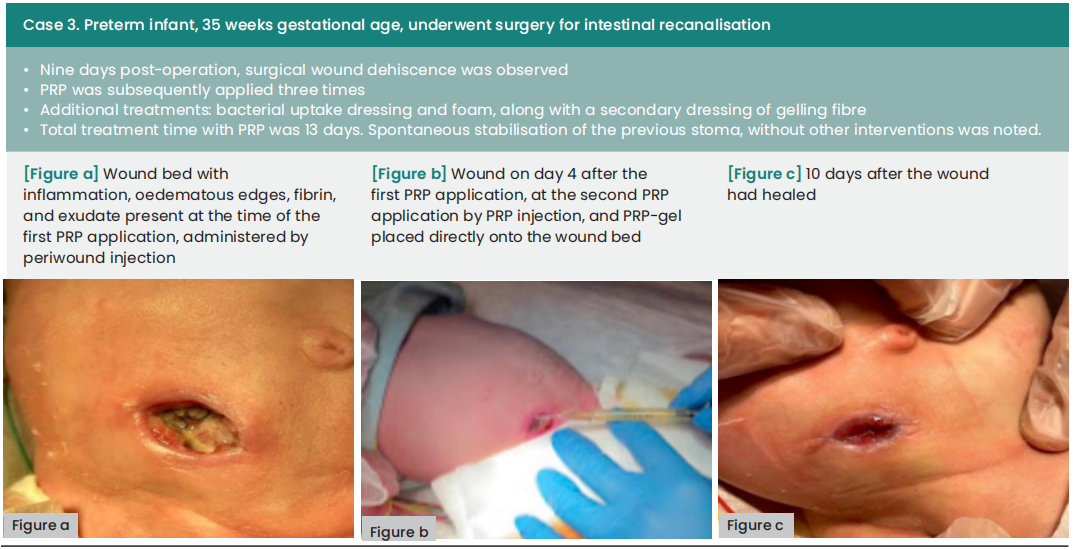

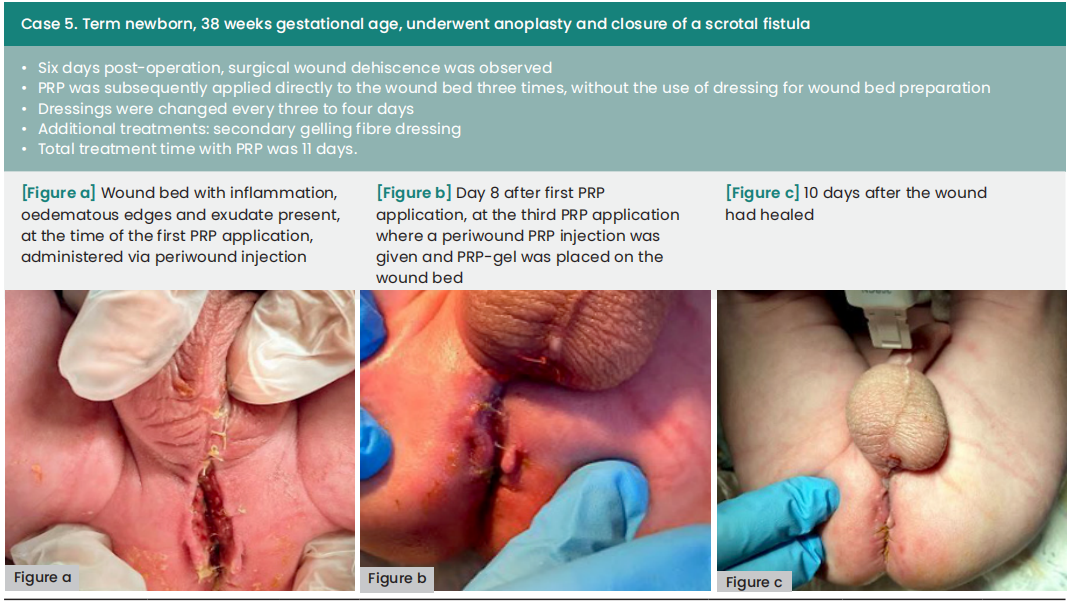

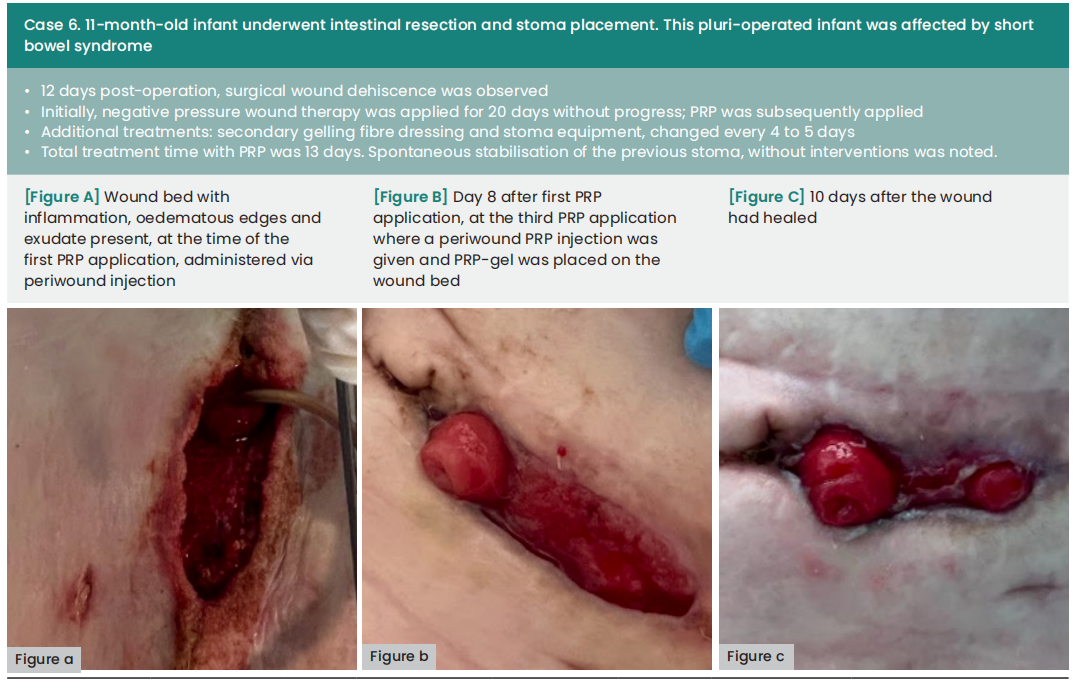

In the cases presented below, PRP was administered following wound bed preparation using advanced dressings or to aid in wound closure after negative pressure wound therapy. The application of PRP involved both injection and topical application around the periwound area, conducted in settings ranging from intensive care units to surgical wards and outpatient clinics. All of the local treatments described were supported by specific systemic antibiotic therapies.

The average duration between wound dehiscence and intervention was ten days (range: 6—60), with a median of nine days from dehiscence detection to the first PRP application (range: 0—21). The average interval between PRP applications was four days. Subsequently, all wounds achieved complete healing following at least two PRP applications, with an average treatment duration of 12 days (range: 8—18).

Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from both parents and patients for the capture and use of photographs, taken before and after treatment, for all cases. Ethical approval was not required. Patient cases were reviewed in adherence to clinical protocols, and treatment was administered according to individual clinical needs.

Discussion

The use of PRP in wound healing was controversial in the past; however, emerging evidence supports PRP as a promising treatment modality for wound healing (Okudo et al, 2021). The positive outcomes associated with the use of PRP are due to the alteration of the pathological process, which is influenced by growth factors, leading to a visible change in wound appearance from chronic to acute. Platelet gel effect consists in promoting appropriate granulation tissue for regeneration. Not only determines the recruitment of inflammatory cell which had a protective effect towards pathogens, but also determine proliferation of soft tissue cells and this is proven particularly in traumatic wounds, both those caused by burns and those complicated due to local contamination (Menchisheva et al, 2019; dos Santos et al, 2021).

The clinical application of PRP was studied precisely for the good effects on tissues repair and regeneration. Evidence suggests PRP as a treatment strategy, because the platelet-rich plasma has been shown to aid wound healing (dos Santos et al, 2021).PRP application is very widespread in the treatment of complex injury of different aetiologies including diabetic foot ulcers, pressure ulcers, traumatic injuries, burns and infected wounds (Cetinkaya et al, 2018; Cieślik-Bielecka et al, 2018; Hirase T et al, 2018; Zhang et al, 2019; Okudo et al, 2021).

We could not find any evidence of the use of PRP in the paediatric patients, however, our cases show that PRP is saft to use. The available studies on adult patient agreed that there are no treatment-related complications with PRP (Senet, 2003; Driver et al, 2009). There was one reported allergic reaction in a 14 year old, which was a limited skin reaction to calcium citrate, used as an anticoagulant (Latalski et al, 2019).

As shown in our paediatric and neonatal cases, platelet gel use is effective in acute and chronic wound treatment or where healing could be prolonged.

Conclusion

While the concept of using PRP therapy has existed for many decades, its successful application, either alone or as part of adjunctive therapies, has only recently become evident. Currently, PRP remains unfamiliar to many healthcare professionals, potentially hindering patient access to this effective treatment for various conditions.

PRP has shown effectiveness in treating a range of complex lesions. In this series, we successfully treated seven cases of surgical wound dehiscence in a paediatric population.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Biagio Nicolosi and Virginia Carletti contributed equally to this work.

References

1. Attinger CE, Janis JE, Steinberg G et al (2006) Clinical approach to wounds: débridement and wound bed preparation including the use of dressings and wound-healing adjuvants. Plast Reconstr Surg 117(7 Suppl):72S–109S. https:// doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000225470.42514.8f

2. Bielefeld K, Amini-Nik S, Alman B (2013) Cutaneous wound healing: Recruiting developmental pathways for regeneration. Cell Mol Life Sci 70(12):2059–81. https://doi. org/10.1007/s00018-012-1152-9

3. Ceydeli A, Rucinksi J, Wise L (2005) Finding the best abdominal closure: an evidence-based review of the literature. Curr Surg 62(2):220–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cursur.2004.08.014

4. Cetinkaya RA, Yilmaz S, Ünlü A et al (2018) The efficacy of platelet-rich plasma gel in MRSA-related surgical wound infection treatment: an experimental study in an animal model. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 44(6):859–67. https://doi. org/10.1007/s00068-017-0852-0

5. Chetter IC, Osvaldo AV, McGinnis E et al (2019) Patients with surgical wounds healing by secondary intention: A prospective, cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud 89:62–71. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.09.011

6. Cieślik-Bielecka A, Bold T, Ziółkowski G et al (2018) Antibacterial activity of leukocyte- and platelet-rich plasma: an in vitro study. Biomed Res Int 2018:9471723. https://doi. org/10.1155/2018/9471723

7. Driver VR, Hanft J, Fylling CP, et al (2006) Autologel Diabetic Foot Ulcer Study Group. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of autologous platelet-rich plasma gel for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Ostomy Wound Manage 52(6):68–87.

8. Etulian G (2018) Platelets in wound healing and regenerative medicine. Platelets 29(6):556–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/095 37104.2018.1430357

9. Gibble JW, Ness PM (1990) Fibrin glue: the perfect operative sealant? Transfusion 30(8):741–7. https://doi.org/10.1046/ j.1537-2995.1990.30891020337.x

10. Han T, Wang H, Zhang YQ (2012) Combining platelet-rich plasma and tissue-engineered skin in the treatment of large skin wound. Craniofac Surg 23(2):439–47. https://doi. org/10.1097/scs.0b013e318231964a

11. Harrison P (2018) The use of platelets in regenerative medicine and proposal for a new classification system: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost 16(9):1895-900. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.14223

12. Hirase T, Ruff E, Surani S, Ratnani I (2018) Topical application of platelet-rich plasma for diabetic foot ulcers: A systematic review. World J Diabetes 9(10):172–9. https://doi. org/10.4239%2Fwjd.v9.i10.172

13. Landén NX, Li D, Ståhle M (2016) Transition from inflammation to proliferation: a critical step during wound healing. Cell Mol Life Sci 73(20):3861–85. https://doi. org/10.1007%2Fs00018-016-2268-0

14. Latalski M, Walczyk A, Fatyga M et al (2019) Allergic reaction to platelet-rich plasma (PRP): case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 98(10):e14702. https://doi. org/10.1097%2FMD.0000000000014702

15. Menchisheva Y, Mirzakulova U, Yui R (2019) Use of platelet-rich plasma to facilitate wound healing. Int Wound J 16(2):343– 53. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.13034

16. Okudo J, Suh T, Nwagwu VC (2021) Review on use of platelet rich plasma for wound care in medicare population. Wounds International 12(4):10-13.

17. Pang C, Ibrahim A, Bulstrode NW, Ferretti P (2017) An overview of the therapeutic potential of regenerative medicine in cutaneous wound healing. Int Wound J 14(3):450–59. https:// doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12735

18. Rucinski J., Margolis M., Panagopoulos G., Wise L. (2001), Closure of the abdominal midline fascia: meta-analysis delineates the optimal technique, Am Surg; 67:421 – 6.

19. Sandy-Hodgetts K, Carville K, Leslie GD (2013) Determining risk factors for surgical wound dehiscence: a literature review. Int Wound J 12(3):265-275. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12088

20. dos Santos RG, Santos GS, Alkass N et al (2021) The regenerative mechanisms of platelet-rich plasma: A review. Cytokine 144:155560 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2021.155560.

21. Schiavon M, Francescon M, Drigo D et al (2016) The use of integra dermal regeneration template versus flaps for reconstruction of full-thickness scalp defects involving the calvaria: a cost-benefit analysis. Aesthetic Plast Surg 41(2):474. https://doi.org/10.1007%2Fs00266-016-0703-0

22. Senet P, Bon FX, Benbunan M et al (2003) Randomized trial and local biological effect of autologous platelets used as adjuvant therapy for chronic venous leg ulcers. J Vasc Surg 38:1342–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00908-x

23. Takagi N, Kawakami K, Kanno E et al (2016) IL-17A promotes neutrophilic inflammation and disturbs acute wound healing in skin. Exp Dermatol 26(2):137–44. https://doi. org/10.1111/exd.13115

24. Tottoli EM, Dorati R, Genta I et al (2020) Skin Wound Healing Process and New Emerging Technologies for Skin Wound Care and Regeneration. Pharmaceutics 12(8):735. https://doi. org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12080735

25. Xue M, Jackson CJ (2015) Extracellular matrix reorganization during wound healing and its impact on abnormal scarring. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 4(3):119–136. https://doi. org/10.1089%2Fwound.2013.0485

26. Van Ramshorst GH, Nieuwenhuizen J, Hop WC et al (2010) Abdominal wound dehiscence in adults: development and validation of a risk model. World J Surg 34(1):20–7. https://doi. org/10.1007/s00268-009-0277-y

27. Zhang W, Guo Y, Kuss M et al (2019) Platelet-Rich plasma for the treatment of tissue infection: preparation and clinical evaluation. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 25(3):225–36. https://doi. org/10.1089%2Ften.teb.2018.030

This article is from the Wounds UK 2024 | Volume: 20 Issue: 1 by Wound World.