Community nurses play a vital role in the healthcare system, as evidenced by a recent poster released by the Queen's Nursing Institute (QNI; 2023). This poster highlights the diverse responsibilities and expertise of community staff nurses, ranging from sexual health nurses who provide support from preconception to district nurses who care for the elderly. For more information, refer to the QNI poster at: https://qni. org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/CommunityNurses-Touching-Peoples-Lives-Across-theLifespan.pdf.

SAFE CARE, STAFFING AND

MAINTAINING STANDARDS

How healthcare professionals care for patients was highlighted by the Francis Report (2013). The report's findings indicate a lack of care that was exacerbated by a profit-driven culture that prioritised financial gains over patient wellbeing. It also emphasised the need to hold management accountable for disregarding warning signs in favour of meeting productivity targets, serving as a stark warning to the healthcare industry.

In response to the Francis Report recommendations were made to establish safe staffing ratios, which have since been largely implemented in acute care settings. However, despite being six years after the report, safe staffing for district nursing has yet to be clearly defined.

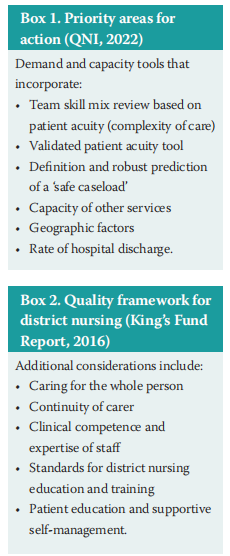

In 2022, the QNI published a discussion document addressing this issue. The document reviews current challenges and provides guidance on specific safety actions believed to be necessary for improving quality and ensuring future service provision, especially considering the changing patient demographic. Priority areas for action are outlined in Box 1, which align with the findings of the King's Fund Report (2016). The King's Fund Report refers to previous research conducted by the QNI and presents a quality framework for district nursing, as described in Box 2.

CARING FOR VULNERABLE PATIENTS

Nursing in the community setting is a complex endeavour. As a nurse, you become a guest in the patient's home, which can present challenges related to housing, deprivation and family dynamics. It also involves being part of a multidisciplinary team that includes the patient's general practitioner, social care professionals, acute care providers and third-sector organisations, each of which contribute different aspects to the patient's care pathway. Because the care system is complex and difficult to navigate, it is understandable that some elderly patients may feel vulnerable.

In complex cases, the district nursing team serves as the constant presence and the central point of coordination for patient care. However, it is important to recognise that each patient is an individual with a unique personality and preferences and acknowledging and respecting these aspects is crucial for providing a quality service. Care should be humanised, compassionate, empathetic and not constrained by market forces (Flynn and Mercer, 2013).

In the community nursing setting, colleagues often share stories of managing “difficult clients”. Unfortunately, our professional response is to manage the behaviour without exploring the factors which may underlie them. However, this is often due to a lack of time to investigate, as opposed to a lack of professional curiosity.

Patient behaviour is complex and influenced by personal beliefs and values. That said, recent attrition rates, failure to retain staff, retirements and reductions in student numbers have led to an increased number of nursing vacancies (The Health Foundation, 2019). It is important to note that this report, published by The Health Foundation was published prior to the pandemic, and the subsequent recovery period has had a negative impact on published figures, with community nursing being particularly affected. Many staff members are feeling broken, carrying the scars of moral injury. Despite the support provided by occupational health, safeguarding, psychology and wellbeing teams, some have made the difficult decision to leave their positions.

USE OF DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY

A recent survey (QNI, 2023) indicates that digital technology has become deeply ingrained in community nursing practice, with community staff members using technology for various purposes. The use of technology can influence when and where nurses interact with patients. The COVID-19 pandemic expedited the adoption of technology, particularly in terms of remote consultations.

When evaluating the digital literacy of community nursing staff, the survey found that they exhibited a high level of proficiency. They recognised the potential benefits of new applications that could greatly impact areas like wound care and long-term conditions. However, the survey revealed that many respondents feel that the implementation of digital technology in practice is inadequate and fails to save time, despite time being a precious resource. They also expressed frustration with the design and functionality of the technology currently available.

ACKNOWLEDGING HUMAN ERROR AND

UNWARRANTED VARIATION IN CARE

Human errors occur because of several factors in healthcare and the management of non-healing wounds is no exception. Several factors contribute to these errors. Firstly, the vast number of research studies and recommendations released make it impossible for healthcare professionals to stay updated on all publications that should inform their care decisions.

Secondly, care is not delivered in isolation, it is delivered in many microsystems that interconnect. Efficiencies in one system can impact another and thereby expose vulnerabilities that can lead to errors especially if only one element of care has been studied or considered.

Thirdly, human beings are susceptible to cognitive bias and this affects our ability to reliably and accurately solve problems in a reproducible manner.

Additionally, our working memory has limitations, which can be further compromised by distractions, stress and sleep deprivation, making us more prone to errors.

After recognising the significance of human factors in patient safety, the healthcare industry now emphasises human factors training as a crucial component of both pre-and post-registration education (Norris et al, 2012).

CONTINUITY OF CARE

The King's Fund, authored by Freeman and Hughes, in 2010 explored the concept of continuity of care and highlighted its significant contribution to improving patient experience. The paper identified

two important components of continuity of care: relationship continuity and management continuity.

Relationship continuity refers to the establishment of a therapeutic relationship between a clinician and a patient, enabling ongoing management of the patient's care. This type of continuity ensures consistent management, including the provision and sharing of information for care planning and coordination. It also reduces the need for patients to repeat previously shared information to multiple caregivers. Relationship continuity is highly valued by both healthcare professionals and patients and is associated with reduced costs and improved patient outcomes, as supported by research. Gray et al (2019) revealed unwarranted variation in community wound care services, which was linked to the underuse of evidence-based practices. The study found that staffing and financial pressures negatively impacted continuity of care, availability of wound care services and workloads.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) emphasises the importance of improving patient experience as a fundamental aspect of care (NICE, 2012). Maintaining continuity addresses some of the concerns and is more consistent in primary care as compared to secondary care. It is however acknowledged that current workforce pressures are often cited in the failure to achieve continuity when speaking to community teams.

PATHWAY FOR IMPROVING THE TREATMENT OF NON-HEALING

WOUNDS IN THE COMMUNITY

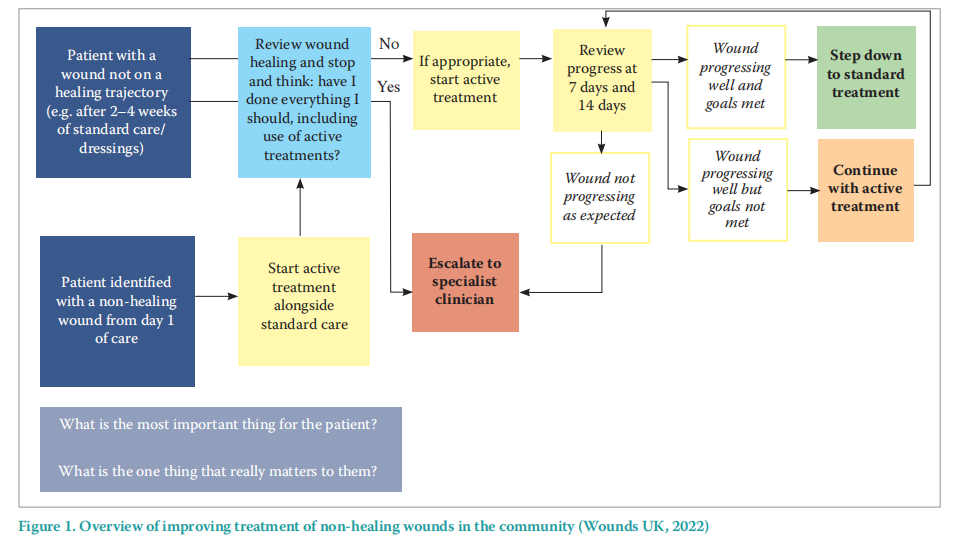

Non-healing wounds can pose a significant burden on patients, resulting in pain, diminished quality of life, and increased healthcare costs. The Best Practice Statement by Wounds UK (2022) addresses the care of non-healing wounds, aiding staff in identifying patients at risk of such wounds.

To mitigate these challenges, care pathways have been implemented using active treatment such as single-use Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (sNPWT), as discussed in the second article of this series (Dowsett, 2023). These pathways strive to establish standardised guidelines and protocols, aiming to address the patient's needs, enhance care quality and reduce the likelihood of errors.

Following the pathway (Figure 1; Wound UK, 2022), when a wound fails to respond positively to standard care and dressings within 2 to 4 weeks, there is a need for alternative approaches. Therefore, the treatment plan is reassessed, and if appropriate, active treatment is initiated. Weekly monitoring and assessment of the wound's progress are vital throughout the treatment process and depending on the wound's progression, adjustments to the active treatment plan may be required, such as stepping down to standard treatment, continuing with active treatment or escalating the patient to a specialist clinician.

CASE STUDY

To preserve confidentiality, Edie is a pseudonym.

Edie is an elderly woman who is under the care of the district nursing team who visit her home twice a week to attend to her bilateral venous leg ulcers. Edie has no carers and previously handled her own food shopping until her leg ulcers made moving and wearing shoes difficult. Instead, her daughter is doing her weekly shopping, and making Edie more aware of her increasing frailty and potential reliance on others. She has shared that she sleeps on a recliner chair downstairs and refuses to go outside because she is afraid of falling due to her bandages.

The nursing staff assigned to Edie recognised that she responded best to a specific pair of nurses. To ensure continuity of care and effectively meet her needs, they implemented a named nursing model, with these two nurses carrying out 80% of her visits. This personalised approach aimed to provide Edie with the best possible care.

Initially, Edie's legs were oedematous, but compression bandages helped to reduce the swelling. She tolerated the bandages well for four weeks before refusing them because they were too tight. Despite her expressed dissatisfaction with the slow healing of her wounds, she admits that the bandages have helped.

Following the pathway, the nursing team assessed Edie’s ulceration, which was well-defined in one area of both limbs (proximal to the medial malleolus), it was not infected but had a moderate level of exudate and was not on a healing trajectory after four weeks of standard care/dressing. Edie’s wound healing progress was then reviewed and it was noted that active healing had not yet been included in her treatment plan. Therefore, considering Edie's suitability for active treatment, sNPWT was initiated to stimulate healing.

At all points in the process, the nurses maintained open communication with Edie, ensuring she was kept informed and involved in decision-making. Weekly wound measurements and photographs were taken, and wound area reduction was calculated to provide valuable feedback on wound progress to both Edie and her daughter, instilling confidence and reassurance.

The nurses tapped into Edie’s love of clothing and found compression garments that matched her favourite outfit enabling her to independently don and doff them. Recognising the importance of mobility in Edie's overall well-being, she was also referred to a community physiotherapist and orthotist, with the medium goal of getting Edie back into her usual bed and out of the house and into her garden. The long-term goal is to get her back on the bus and shopping on her own.

Edie’s wound healed within 6 weeks after using sNPWT for 2 weeks and then an adherent foam dressing in conjunction with hosiery. The use of hosiery to aid healing helped Edie see the benefit of using compression to prevent future ulcers, and she continues to wear them.

The physiotherapist and occupational therapist helped Edie gain confidence and suggested some social prescribing to connect Edie with some community groups that interested her. With her regained mobility and independence, Edie has returned to sleeping in her own bed and has established a routine of removing the stockings at night and putting them on again in the morning. She now actively participates in events held at a nearby community centre. Her family visits have also resumed, and her activity and engagement levels have returned to pre-pandemic levels.

CONCLUSION

The complexity associated with caring for patients in a community setting has been explored in this article. By sharing Edie’s story, I hope to illuminate possible reasons behind potentially challenging cases and behaviours. The nursing team recognised the patient's vulnerability and demonstrated the courage to address it in this instance and in future cases. As a result, the outcomes were patient-centred, aligning with both Edie’s objectives and nursing goals.

If the team had initially responded in a similar manner to the other professionals involved, the outcome could have been very different. Instead, the patient was offered considerate care that took into account her individual needs while being grounded in evidence-based care. Delivering highquality care requires emotional and courageous commitment. It necessitates staff members who are curious, reflective, emotionally intelligent, resilient and determined to make morally and professionally sound choices in care delivery.

Although this practice may seem like extra work, particularly in situations where nurses are already pressed for time, in reality, it is not. It simply entails a change in mindset, shifting from passive management to active treatment. This change in approach ultimately leads to time savings, both in the short term by reducing the frequency of dressing changes, and in the long term by promoting improved patient outcomes, such as the healing of wounds that eliminate the need for further dressing changes. At the heart of this approach lies the fundamental principle that everyone, including nurses and patients, deserves to be treated with unconditional regard. Embracing this principle not only establishes a solid foundation but also becomes a powerful combination when placed at the core of nursing care.

REFERENCES

1. Dowsett C (2023) Active treatment of non-healing wounds in the community: Identifying people at risk of non-healing wounds. Wounds UK 19(2):46–50. https://tinyurl.com/msty79mw(accessed 3 October 2023)

2. Flynn M, Mercer D (2013) Is compassion possible in a market-led NHS? Nurs Times 109(7):12–4

3. Francis R (2013) Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry: Executive Summary. http://tinyurl.com/lcsocyg (accessed 3 October 2023)

4. Gray TA, Wilson P, Dumville JC et al (2019) What factors influence community wound care in the UK? A focus group study using the Theoretical Domains Framework. BMJ Open 9: e024859. https://doi. org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024859

5. Health Foundation (2019) A critical moment: NHS Staffing trends, retention and attrition . https://tinyurl.com/45hhkk4m (accessed 3 October 2023)

6. Kings Fund (2010) Continuity of Care and the patient experience Continuity of care and the patient experience https://tinyurl.com/ yc6nchnd (accessed 3 October 2023)

7. Kings Fund (2016)Understanding quality in district nursing services: Learning from patients, carers and staff. https://tinyurl.com/3ccjhta5 (accessed 3 October 2023)

8. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2012) Patient experience in adult NHS services: improving the experience of care for people using adult NHS services. https://tinyurl.com/9ppjcwd (accessed 3 October 2023)

9. Norris B, Currie L, Lecko C (2012) The importance of applying human factors to nursing practice. Nurs Stand 26(32):36–40. https://doi. org/10.7748/ns2012.04.26.32.36.c9044

10. Queens Nursing Institute (2022) New Workforce Standards for District Nursing Launched. https://tinyurl.com/mr5c7y66 (accessed 3 October 2023)

11. Queens Nursing Institute (2023) Community nurses touching peoples lives across the lifespan. https://tinyurl.com/yt3y5s2a (accessed 3 October 2023)

12. Wounds UK (2022) Best Practice Statement: Active treatment of nonhealing wounds in the community. Wounds UK https://tinyurl.com/ msty79mw (accessed 3 October 2023)

This article is excerpted from the Wounds UK | Vol 19 | No 4 | 2023 by Wound World.