What is already known

- Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers, including device-related pressure ulcers, are used as a proxy measure for nursing care quality and safety.

- Reporting pressure ulcers is inconsistent between healthcare professionals, organisations and healthcare systems.

-

Awareness of factors affecting reporting practices allows for targeting quality improvement interventions.

What this paper adds

- The fear of potential consequences to the healthcare professional and institution may result in incomplete incident reports.

- To motivate staff to report medical device-related pressure ulcer incidents, the real-life impact should be visible, and feedback given.

- There is a need for clear policy and guidelines for reporting medical device-related pressure ulcers.

1. Background

A pressure ulcer is defifined as localised damage to the skin and/or underlying tissue as a result of pressure or pressure in combination with shear. Pressure ulcers usually occur over a bony prominence but may also be related to a medical device or another object (EPUAP NPIAP & PPPIA., 2019). Pressure ulcers are categorised depending on the depth of damage to the skin and sub-dermal tissues. The lowest category has intact skin, and the highest presents with a deep wound down to the bone (EPUAP NPIAP & PPPIA., 2019). These multifaceted, complex wounds are present in all healthcare settings posing a significant burden to patients and healthcare systems worldwide (Shahin et al., 2009). They are associated with high mortality, morbidity and need for extended hospitalisation (Bennett et al., 2004; Shahin et al., 2009). Individuals who suffer from pressure ulcers have a diminished quality of life, suffer from pain (Gorecki et al., 2012), and often psychosocial issues (Essex et al., 2009; Galhardo et al., 2010). The estimated costs of managing pressure ulcers vary across different countries, with recently cited annual expenditures of approximately $26.8 billion in the US (Padula and Delarmente, 2019) and £531 million in the UK (Guest et al., 2018).

In recent years there has been a growing interest in medical devicerelated pressure ulcers, where the skin damage takes on the shape and/ or the pattern of the medical device (EPUAP NPIAP & PPPIA., 2019). Although there are some disparities in the definition of a medical device, the World Health Organization defines it as any device with the intended primary mode of action to be on the human body used for medical reasons (WHO, 2003). Devices most commonly implicated in medical devicerelated pressure ulcer development include nasogastric and endotracheal tubes, non-invasive ventilation masks, cervical collars, anti-embolism stockings, and casts (Apold and Rydrych, 2012; Barakat-Johnson et al., 2017; Black et al., 2010). A seminal paper published in 2010 by Black et al. revealed that over a third of hospital-acquired pressure ulcers were medical device-related and that patients with devices were 2.4 times more likely to develop a pressure ulcer of any kind. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis undertaken by Jackson et al. (2019) estimated the pooled incidence of medical device-related pressure ulcers was 12%, and prevalence was 10%, with some studies reporting prevalence as high as 45% depending on the setting. These device-related pressure ulcers affect individuals of all ages, from neonates to the elderly.

Healthcare providers use prevalence studies to monitor the quality of care, where a count of all pressure ulcers over a given time is reported. This includes those present on admission to a healthcare facility and those acquired during the hospital stay. In the latter case, the facility acquired pressure ulcer rates are used as a measure of the quality and safety of care because they can be attributed to the fundamental practice by healthcare professionals. Pressure ulcers are routinely reported to facilitate learning from incidents and prevent further events (Pfeiffer et al., 2010; Francis, 2013). In some countries, such as the USA, hospital-acquired pressure ulcer rates are linked to reimbursement and accreditation for healthcare organisations (Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS], 2019).

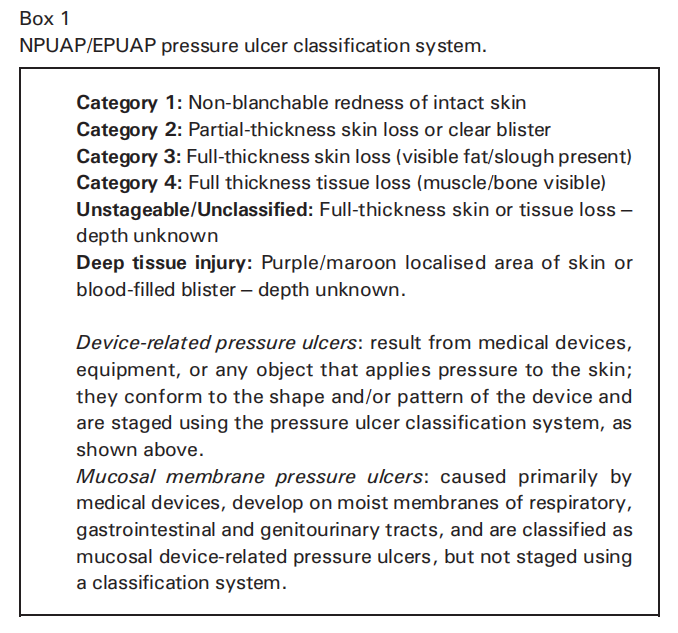

Reporting practice can occur at several levels, including unit (department), hospital, and national. At a healthcare facility and national level, the emphasis is on those pressure ulcers considered serious incidents, including categories 3 and 4, and unstageable (see Box 1). Accurate and consistent documentation and reporting provide the ability to compare data between institutions and track changes over time following the implementation of preventative strategies (Gefen et al., 2022). However, as identified in the literature, there is a lack of consistency in reporting pressure ulcers (Fletcher and Hall, 2018; Coleman et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2016). Reporting medical device-related pressure ulcers is a relatively new process, and it is underdeveloped and inconsistent between organisations and countries (Crunden et al., 2021). There is, however, an opportunity to implement consistent reporting across organisations, although a fundamental understanding of the barriers and facilitators to reporting is still lacking.

Prior to implementing a novel reporting tool, it is essential to understand what factors affect the clinicians' reporting practice. These factors (determinants of practice) might prevent (barrier) or enable (facilitator) reporting (Flottorp et al., 2013). Consequently, identifying them may lead to more effective and efficient implementation of improvements in how and what data are reported and ‘bridge the gap’ between research and clinical practice (WHO, 2006). Thus, this study aimed to establish the factors affecting the reporting of medical device-related pressure ulcers in clinical practice through a series of semi-structured interviews with international experts in the field.

2. Methods

This study used a descriptive explorative approach incorporating semi-structured interviews with clinicians and academics experienced in tissue viability, wound assessment and/or reporting, and a medical devices industry representative. Interviews were undertaken online (Skype and Zoom), via telephone, and face-to-face, which enabled data collection from a vast geographical area and permitted exploration of different reporting systems. All interviews were undertaken between October 2019 and February 2020. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007) were followed in this paper, see Additional file 1.

2.1. Participants

Participants were recruited via international wound care organisations, including the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance, European Wound Management Association, and the National Health Service Improvement Wound Care Strategy Group. Participants were purposefully sampled to represent a range of experiences and be experts in tissue viability and/or wound assessment or reporting, in addition to possessing a good working knowledge of policy and practice stemming from their leadership roles. Sample size or saturation did not guide the research. Instead, we looked to include representatives from as many countries as possible to give a general overview of factors impacting reporting practices.

2.2. Data collection

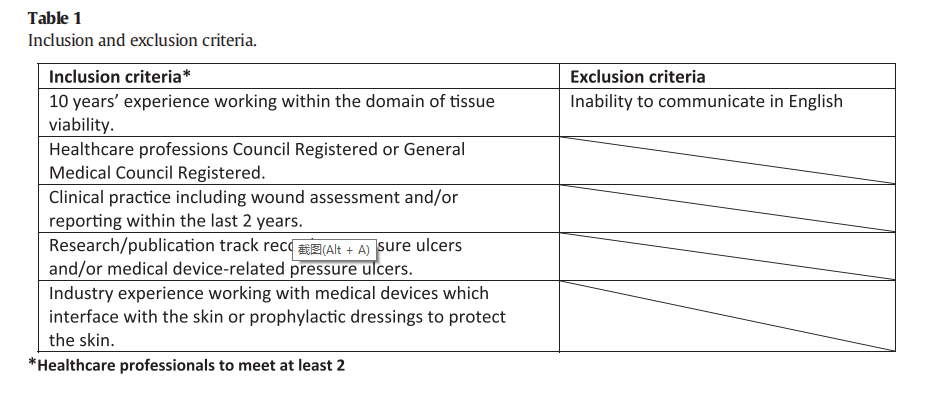

Organisations' representatives recruited gatekeepers, who identified potential study participants representing different regions under their membership. The lead researcher initially contacted all potential interview participants via email to present the study and its aims. The researcher confirmed eligibility (Table 1) and scheduled an interview if they expressed willingness to participate. Written consent was collected before the interview took place.

All interviews were undertaken by the lead researcher and audio recorded. Transcripts were not returned to participants for review, but the lead researcher checked them against the original recordings to ensure accuracy. Interviews were guided by a semi-structured topic list (see Additional file 2) developed based on identified research gaps and reporting practices (Crunden et al., 2021). Interviews lasted between 30 and 60 min, with the telephone interviews being the shortest.

2.3. Data analysis

Thematic analysis with a codebook approach was used to analyse the data (Braun and Clarke, 2021). Initially, the researcher immersed themselves in the data through systematic reading and familiarisation. Open coding was undertaken independently by the main researcher and cross-checked by the other team members. This was followed by focused coding. The initial codes making the most analytical sense were chosen to categorise data (Charmaz, 2014), and themes are presented as domain summaries (Braun and Clarke, 2021). Coding and analysis started immediately after the first interview, with new data added to the analysis as it emerged. Data analysis was supported by the NVIVO software (NVIVO 12 PRO, QSR International). The lead researcher maintained a reflexive journal to examine own values, identity and background due to their potential to affect the research process (Polit and Beck, 2017), and an audit trail was developed.

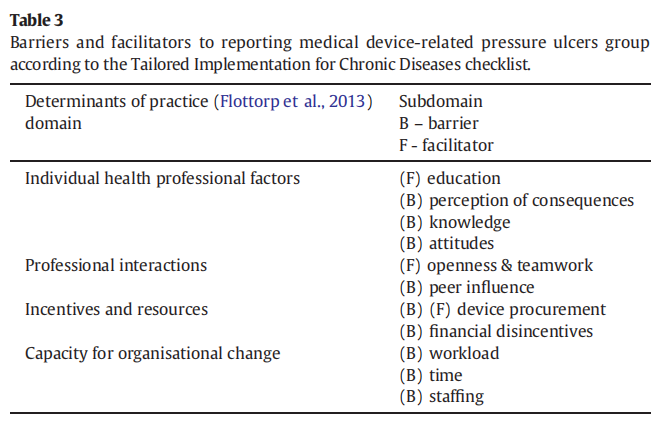

To systematically report barriers and facilitators of medical devicerelated pressure ulcer reporting, the Tailored Implementation for Chronic Diseases checklist was used (Flottorp et al., 2013). The Tailored Implementation for Chronic Diseases checklist constitutes seven domains: guideline factors, individual health professional factors, patient factors, professional interactions, incentives and resources, capacity for organisational change, and social, political, and legal factors. The checklist was developed through a systematic review and consensus process. This generic tool allows screening the most pertinent determinants of practice to focus the implementation strategy and ensure the subsequent change initiative is successful (Flottorp et al., 2013). The developed themes were entered into the Tailored Implementation for Chronic Diseases checklist matrix as sub-domains and highlighted as a barrier or facilitator for the reporting practice (Table 3).

2.4. Human research ethics approvals

The study protocol was approved by the University of Southampton Research Integrity and Governance Board (ERGO II 49718) prior to recruitment. The study protocol followed the Declaration of Helsinki (WHO, 2013).

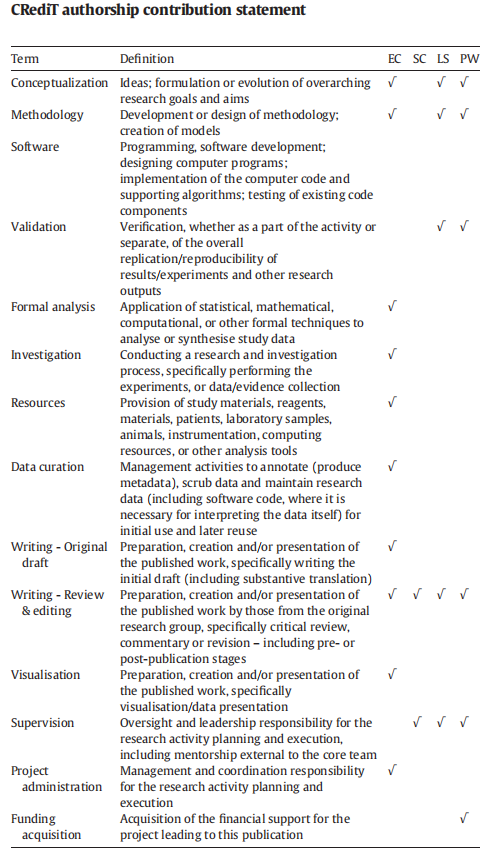

2.5. Research team

The main author (EAC), a female PhD-level researcher with experience in qualitative research methods, interviewed the participants. There was no prior relationship between the researcher and participants. The other team members, who all have experience in qualitative research, crosschecked a small subsection of transcripts, coding and analysis (LS, SBC and PRW) to ensure consistency and accuracy.

3. Results

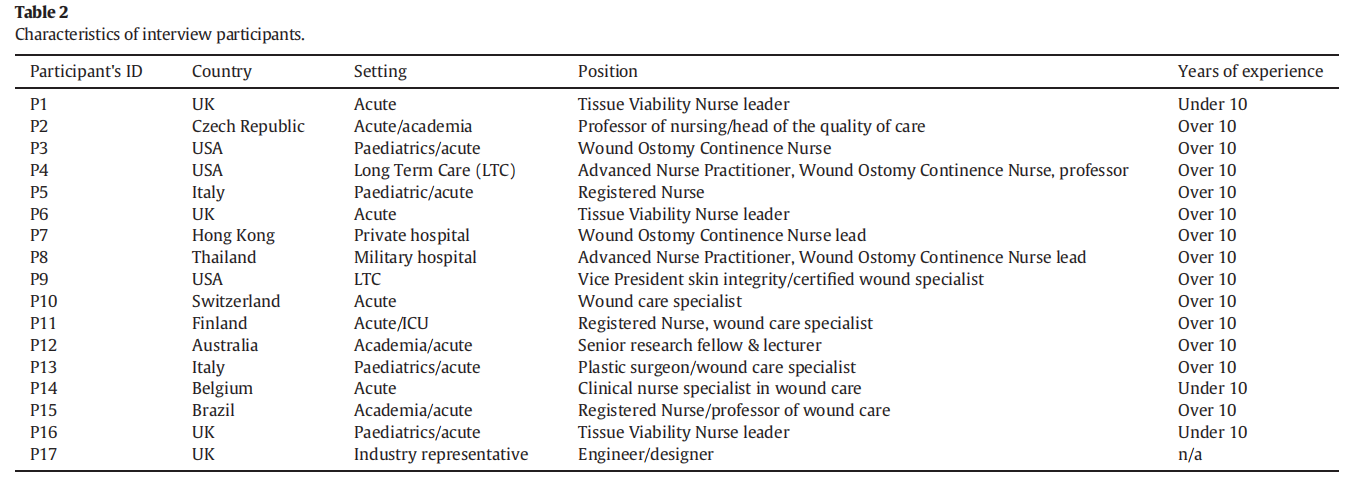

Seventeen participants representing eleven countries took part in the study, and their characteristics are presented in Table 2. Most participants (14/17) identified themselves as tissue viability/wound specialists/wound and ostomy care nurses. Eleven out of fourteen healthcare professionals had more than 10 years of clinical experience in tissue viability. The majority of interviews (11/17) were undertaken using Skype, telephone (3/17) and Zoom (2/17). One interview was conducted face-to-face.

3.1. Determinants of practice and themes

Themes developed inductively during thematic analysis were examined against the Tailored Implementation for Chronic Diseases checklist and reported as sub-domains. Our results were grouped in four of these domains: Individual health professional factors, professional interactions, incentives and resources, and capacity for organisational change (Table 3).

3.1.1. Individual health professional factors

3.1.1.1. Education. Specialist nurses in this study suggested that educating nurses and other clinical staff to be able to correctly identify medical device-related pressure ulcers would improve reporting of these wounds. Participants indicated that often a quality improvement educational project led to such improvements: “So after I rolled out the project in 2017 for the BiPAP [Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure] prevention, they [staff] started to recognise [the medical device-related pressure ulcers] and they know how to report them” (P7).

3.1.1.2. Perception of consequences. Participants reported that nurses are often nervous about missing a pressure ulcer, and hence they report anything that might be pressure damage. On the other hand, there is the worry that the unit will be considered to have ‘too many’ of those wounds and be judged negatively: “So even though it's not a financial impact, the wards and ourselves feel that most keenly” (P1). There is also a notion that the person reporting a pressure ulcer is somewhat responsible for its development. Similarly, if an agency nurse discovers a pressure ulcer, they might weigh the pros and cons to reporting: “What's the risk for me if I report it and it wasn't reported[before], are they going to think I did it? What does that mean for my job?” (P9).

3.1.1.3. Knowledge. Participants reported a lack of knowledge relating to medical device-related pressure ulcers as one of the main barriers to reporting. Medical device associated wounds are often not recognised or not identified as pressure ulcers. Category 1 medical device-related pressure ulcers may not be reported beyond the institutional system because staff are unsure of the diagnosis. The clinical staff also lack knowledge of the risk factors and might not appreciate the long-term consequences of device-related skin damage. Another barrier discussed was the disparity between educational medical device-related pressure ulcer publications, and devices that are in clinical use in less-well funded healthcare systems: “Some devices that we see in the picture, or the literature are not used in [our country]” (P15). The knowledge might not be transferable between high- and low-income settings.

Despite knowing that device harm can be reported to regulatory bodies, clinicians involved in direct patient care did not consider making such reports: “I might have actually forgotten that I could make complaint myself” (P11). Reports concerning medical devices were considered managers' responsibility and undertaken according to organisational policies. However, despite following the prescribed procedures by the clinician, the internal report may not be escalated as presumed: “[Reporting a medical device] was something that I thought that Risk [hospital department responsible for reporting to MHRA (Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency)] did. And then I found out that Risk didn't [report]” (P1).

3.1.1.4. Attitudes. There was a belief that medical device-related pressure ulcers are not an issue on general wards. In some cases, clinicians reported that these wounds do not occur often: “I don't think it's a huge problem in our hospital” (P14), and their focus was on the prevention of traditional pressure ulcers. Medical device-related pressure ulcers may also not be reported because of the perception that after relieving the patient from the device, the pressure ulcer category 1 or 2 will heal quickly and therefore is not worth reporting: “I think if you've got something, say, on the ears or the nose and the patient then had that tubing or mask removed, they're just going to heal up fairly quickly and go away, I don't think all of those [pressure ulcers] are reported” (P1).

Medical device-related pressure ulcers on critical and intensive care units were reported to have become normalised and perceived as something that cannot be avoided. Medical devices are expected to cause skin harm because they always have done: “I think that a lot of the time people just expect them [medical devices] to cause problems and they've always caused problems. So people don't think of it as a problem because it's just expected” (P1). Moreover, because incidents of medical device-related pressure ulcers are expected, not all of them are being reported: “People only report the most serious issues and not everyday issues” (P4).

Medical devices regulatory authorities were identified to be predominantly supporting the management of serious incidents relating to device malfunction or patient injury, where the incident itself first has to be investigated by the organisation before it is escalated: “If it's urgent [problem with a device], it will require an urgent withdrawal in our hospital. But if it's indeed serious, then it will be reported to the higher instances for sure” (P14). In addition to the severity of the incident being a primary factor in reporting, there is a perception that it should be more than one event. Otherwise, it will not be taken seriously by the regulatory body: “They [the regulatory body] might think the device is not dangerous if they didn't get another complaint. So, they don't have to be focused on it. If there were more cases, then they have to do something, take some action” (P2).

However, in countries that have established procedures for submitting reports to those bodies, doubt in their willingness to be proactive in acting upon reports has emerged: “I think it is possible to communicate with them [regulatory authority], but they are a bit of a ‘toothless tiger’, and they've been exposed and criticised in recent years (…). I'm not sure about their effectiveness, to be honest. I'm not sure if that would be the first port of call if there were a complaint about devices” (P12). Moreover, transparency has been questioned as well: “It turns out that the manual medical manufacturers actually have a different site, that they report data to the FDA [United States Food and Drug Administration] that is not accessible by the public. So even if we check the MAUDE [Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience] site, it may not be comprehensive because of this protected site between the FDA and the manufacturers” (P4).

3.1.2. Professional interactions

3.1.2.1. Openness and teamwork. Openness and lack of fear of reporting,followed by a process of investigation and feedback, means staff can learn from incidents and improve practice: “How our policy is, is to learn and practice and do better the next time. And that is not a shame that will cause any problem. This is a problem [incidents of medical device-related pressure ulcer] related to the whole system of care, not just to a single person” (P13). This climate of openness is also about receiving positive feedback, so the staff can celebrate and share good practices. Involving other clinicians, such as doctors, opens another communication channel. Nurses being able to ask questions about how they treat patients make medical device-related pressure ulcers a team problem, not solely a nursing problem. This gives the feeling of working in a team and learning with/from others: “We can say ‘doctor, I have this lesion, and I'm treating it this way. Is it the right way?’ We are not isolated, there's a team” (P5).

Nonetheless, it might be difficult for a junior member of staff to verbalise opinions that are opposite to the more senior staff: “Another problem is also that even if they report as medical device-related pressure ulcer, it won't be accepted and the rest of the group in the unit will say ‘oh you're joking. It's not like this.’ I had a student from master's degree who came to me and said: ‘I want to report it and they said I was stupid, and that it was not true [the presence of medical device-related pressure ulcer]’” (P2).

Open communication between wound nurses and staff from operating theatres was mentioned to be especially important. Operating theatres have specific ways of positioning the patient, especially prone position is shown to increase the risk to patients developing medical device-related pressure ulcers: “Sometimes they do the spinal surgery for more than 10 hours, but they can't turn the patient back and see [the] face. Sometimes maybe they move a little bit of the patient, but they never know whether it [the head] is in the right position on the device. It is a bit difficult for us because we are not operation room nurses, and we usually have to use imagination about what had happened to the patient with the devices” (P7).

3.1.2.2. Peer influence. Despite the emphasis of policies on safety and learning from incidents, the blame culture on hospital wards still exists: “Although we concentrate very much on the learning, (…) I think when you've suffered years, if not decades of the blame culture, you can't get rid of that overnight” (P1). Participants agreed that a shift in this attitude requires ongoing education.

3.1.3. Incentives and resources

3.1.3.1. Device procurement. Device procurement can be both a barrier and a facilitator to reporting. Our participants described the procurement as cost-driven, which can be a barrier to reporting: “So there's a very cheap one [dressing available from a supply chain], medium one and a little bit better one. And then we have to use one of them because you can't get in any others. It's causing an awful lot of upset in the tissue viability world because the concern is it will be the same with devices” (P6). The inability to see a real-life impact of reporting on the range of medical devices available for patient care can have a negative impact on clinicians' reporting behaviour.

However, the inner context of the organisation's ability and readiness to dedicate resources to support medical device-related pressure ulcer reporting may also be a facilitator. It may support the reporting practice since the feedback might have an impact on what devices are purchased by the organisation: “There's, of course, the hospital purchase office They are the ones that decide which medical device we can use in the hospital, and so we, of course, give the feedback, and then we have to explain and show the evidence that it doesn't work” (P11).

3.1.3.2. Financial disincentives. Fear of reporting exists where the incidence of pressure ulcers is linked with funding. Transparency in presenting pressure ulcer data can also lead to negative organisation perceptions and financial repercussions. Those who are open and frank about pressure ulcer rates can be seen as those who have ‘problems’ with their prevention. In contrast, those who lack transparency can be judged as issue-free: “I have other consultations in U.S. hospitals where typically the Safety Committee or Quality Committee is completely transparent, and their numbers are significantly higher than those institutions in the surrounding area. And everybody thinks that that place has a problem when in fact it's the other places that have no transparency” (P4).

High rates of hospital-acquired pressure ulcers can lead to loss of contracts, loss of accreditation, or lower cost reimbursement. There is also fear of litigation, which is common in countries like the USA: “I don't think a lot of people put that data [adverse event] into the MAUDE database or report it back to the manufacturers because they feel that some of that information is now disclosable in case of a lawsuit. If it stays within the quality department, it doesn't have to be disclosed” (P4).

3.1.4. Capacity for organisational change

3.1.4.1. Workload. In the pursuit of effectiveness and efficiency, patient records have been largely moved into electronic systems. Nonetheless, if a pressure ulcer develops during an inpatient stay, it might need to be reported in more than one: “Nurses have to put that information into a (…) surveillance program that helps the hospital monitor pressure injuries that are being assessed and identified. But it doesn't speak to the integrated electronic health record. Nurses then have to go back to that record (…) [and] they then have to code each of these” (P12).

3.1.4.2. Time. The clinical environment is increasingly busy, and sometimes lack of time may lead to underreporting. Moreover, the length of time it takes to make a report was identified to impact the decisionmaking: “So there's no time. So people only report the most serious issues and not everyday issues” (P4). Competing priorities in intensive care units and workload were also mentioned as factors impacting medical device-related pressure ulcer occurrence and reporting: “is the time which is lacking because they [nurses] have many job bundles that are heavy. And so, there are many reasons why the pressure ulcer is not just the fault of a single person. Is the whole system” (P13).

3.1.4.3. Staffing. Not all institutions employ nurses specialising in tissue viability (e.g. in the Czech Republic or the USA). Also, staff turnover has been pointed at as a barrier to reporting. Organisations may struggle to train everyone to a standard when the changes in staff numbers and abilities are fast and dynamic. Similar problems were discussed outside of acute care: “ [B]ecause of turnover, we experience deficit in education, or we are waiting for education, and the overwhelm of other priorities in the nursing home, sometimes means that [reporting] gets missed” (P4).

4. Discussion

This study identified several barriers and facilitators to reporting medical device-related pressure ulcers in acute and long-term care services. The findings revealed that out of the seven Tailored Implementation for Chronic Diseases checklist domains, our results concentrate on four key areas: (i) individual healthcare professional factors, (ii) professional interactions, (iii) incentives and resources, and (iv) capacity for organisational change. These factors should be accommodated when implementing new guidelines and processes for reporting to improve future practice.

Notwithstanding the lack of comparable publications, parallels may be drawn from the literature on general incident reporting (e.g. medical errors). Despite the policy move towards openness and transparency (Francis, 2013; GMC and NMC, 2015; Wu et al., 2017), clinicians still fear feeling the blame and disciplinary sanctions (Health Quality Ontario, 2017; Pfeiffer et al., 2010; Rashed and Hamdan, 2019), legal penalties (Asgarian et al., 2021; Health Quality Ontario, 2017; Pfeiffer et al., 2010; Rashed and Hamdan, 2019), and experience anxieties over own competency being questioned with potential risk to employment (Asgarian et al., 2021; Pfeiffer et al., 2010; Rashed and Hamdan, 2019). These factors were reported by many of the clinicians participating in the present study and represent significant barriers to reporting medical devicerelated pressure ulcers.

Pressure ulcer prevention and treatment are a multidisciplinary team effort. However, pressure ulcer-related reporting, prevention and treatment have been traditionally assigned to nurses (Samuriwo,2012; Tan et al., 2020; Ursavaş and İşeri, 2020). Due to the pressure ulcer rates being a proxy measure for patients' safety and quality of nursing care, some nurses may feel protective over their unit's data. This may lead to self-censorship by ensuring that the challenging data does not challenge the team. Similarly, a recent study exploring incident reporting by senior and junior nurses reported that junior nurses' reports of pressure ulcers were often downgraded by senior staff (Atwal et al., 2020). Moreover, senior nurses did not support junior nurses' reporting because national reports had a real-life impact on the unit and institution data. However, this study also highlighted that junior nurses might be unaware of senior nurses' decision making about reporting incidents and what quality evidence is required (Atwal et al., 2020). It is reasonable to validate pressure ulcer incident reports by a more experienced clinician. Healthcare providers routinely validate pressure ulcer data (Barakat-Johnson et al., 2018; Chavez et al., 2019; Coleman et al., 2016).

Our study revealed that lack of education is a barrier to reporting medical device-related pressure ulcers. Newly qualified nurses rely on experiential learning to supplement the limited wound care education (Welsh, 2018; Tan et al., 2020). Nursing students in Behnammoghadam et al. (2020) reported that education in medical device-related pressure ulcers was limited. Where the knowledge is lacking, it has been found that nurses turn to their intuition, beliefs and practices, which are not supported by evidence (Welsh, 2018). Limited availability of evidence-based assessment guidelines for medical device-related pressure ulcers and lack of understanding of long-term consequences of these wounds are an important finding since approximately 70% of these wounds develop on a patient's head, face or neck (Apold and Rydrych, 2012), which may negatively impact physical, social and psychological health. Moreover, our study confirms the findings of others, who concluded that staff find diagnosing category 1 pressure ulcers challenging (Beeckman et al., 2007; Defloor et al., 2006). The ability to correctly identify early signs of skin damage, i.e. a category 1 medical device-related pressure ulcer, is important because the progression to a full-thickness wound may happen much faster in comparison to other pressure ulcers due to the lack of adipose tissues in the areas where these wounds develop (Black et al., 2010).

Nurses in our study have also indicated that sometimes only the severest incidents are reported. This finding is similar to Evans et al. (2006), who found that nurses believed that there was no point in reporting ‘near misses’, i.e. an incident that did not cause harm but had the potential to cause injury (Health and Safety Executive, n.d.). This suggests that category 1 medical devicerelated pressure ulcers may not be reported not only because of staff's problems with identification but also as a rationalised act of balancing benefits of reporting and risks of not reporting. Participants in our study also stated that medical device-related pressure ulcers were perceived by staff as an intensive/critical care problem and were somewhat normalised and expected to occur. A similar finding was reported by Behnammoghadam et al. (2020), who explored nursing students' attitudes towards these wounds. This ‘normalisation’ coupled with conscious decisions of some nurses to report only severe pressure ulcers may lead to underreporting hindering improvements in prevention. This would negatively impact the true picture of the burden of wounds and prevent the identification of devices that may benefit from design improvement.

Reporting the medical device-related pressure ulcers was considered a task undertaken within organisational structures. Individual nurses or other clinical staff did not consider reporting to medical device regulatory bodies as laying in their competence. It was recognised that institutional policies must be followed. However, it was also reported that not every organisation possesses one. Interestingly, where reports may be completed according to policies within the institution, it was found that the reports did not actually progress to the medical device authority for investigation. Moreover, regulatory bodies' transparency may be questioned, as well as their proactiveness with dealing with reports (Jewett and de Marco, 2019). This may have a negative impact on attitudes towards reporting to regulatory agencies. The perception that reports do not lead to improvements has been cited as a barrier to reporting in literature (Health Quality Ontario, 2017). As a result, we do not know which devices are most often implicated in patient harm, and their manufacturers cannot work towards improvement. The single interview with the industry representative highlighted a strong willingness to improve reporting of medical device-related pressure ulcers and the view that it could facilitate device improvements. However, further studies with a wider industry participation would be beneficial to substantiate this.

Teamwork was the primary facilitator for reporting in this study. It was linked to a culture of openness and cooperation within a wider multi-disciplinary team. Additionally, a culture of talking about cases, discussions and learning from incidents was highlighted as the reason why incidents were reported and cited as a learning opportunity. This notion of reporting as a way of learning was also named as a facilitator to improvement in other nursing studies (Rashed and Hamdan, 2019). Nonetheless, in the light of reports from other participants in our study, it is clear that ‘knowing’ does not always equal ‘doing’ when staff are unable to classify pressure ulcers, and barriers to reporting are present.

Fear of financial consequences for the organisation was quoted as a substantive barrier to reporting within our study. Hospitalacquired pressure ulcers, which medical device-related pressure ulcers mostly are (Clay et al., 2018; Ham et al., 2017), can bear the risk of a loss of reimbursement, contract or accreditation in some countries (Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS], 2021). In the USA, pressure ulcer categories 3 and 4 are considered never events (Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS], 2019), and the organisation's cost of managing those wounds is not reimbursed (Kline et al., 2020). This may lead to under-reporting of those ulcers where there might be some uncertainty in the wound staging (Weller et al., 2018). Squitieri et al. (2018) found that these severe pressure ulcers were more likely to be reported as present on admission. Although those studies were concerned with pressure ulcers not related to medical devices, there was concern that financial consequences lead to altered reporting. In doing so, clinicians may feel they protect their organisation from hardship and manage its public image (Weller et al., 2018).

Currently, healthcare organisations must deliver high quality and safe care on a budget. The procurement of devices was reported to be cost-driven. Although organisations often form groups to improve their purchasing position, participants felt the cost might limit the quality of devices that can be used for patients. Although clinicians tried to influence decisions made by procurement offices by reporting problems (including medical device-related pressure ulcers), clinicians felt disillusioned with the impact such reports have. There are no publications discussing if more expensive devices are better in preventing medical device-related pressure ulcers. However, many devices have not changed for decades in design principles or materials. Consequently, often generic sizes are used with stiff polymer materials, which do not accommodate the vulnerability of the underlying skin and soft tissues (Bader et al., 2019; Gefen et al., 2020).

Results of our study confirmed that reporting gets missed, or decisions are made as to which incidents to report in the face of issues of workload, time and staffing resources (Evans et al., 2006). Competing priorities act as a barrier to reporting due to staff having to decide which task to give priority to. Possible factors impacting those decisions are the time it takes to complete the task and the ‘immediate effect’ it has on the patient (Kalisch, 2006). In many cases, participants talked about system-based reporting barriers, which corroborates findings of other studies (Asgarian et al., 2021; Evans et al., 2006; Pfeiffer et al., 2010). Moreover, our participants reported that there are no specialist wound care clinicians or staff educated in pressure ulcers in some care settings, which may negatively impact the organisation's ability to recognise and report medical device-related pressure ulcers.

4.1. Strengths and limitations of the study

To our knowledge, there is no other study looking specifically into barriers and facilitators to reporting medical device-related pressure ulcers. Our main strength is the inclusion of participants from different countries and healthcare settings. Collecting a wide array of experiences and opinions allows the findings to be trustworthy and valid.

Nonetheless, our recruitment strategy resulted in the participation of individuals with a vested interest in medical device-related pressure ulcers. This study's participants were mainly specialist nurses who held a leadership role or were also involved in research and teaching. This enabled us to get an overview of the current clinical practice from a leadership point of view. However, not involving the ‘bedside’ nurses in this study might have limited our results relating to factors having a ‘real-life’ impact on clinical reporting practice. Due to medical devicerelated pressure ulcers being most prominent in intensive and critical care, our participants mainly represented those settings; this is another limitation to this study. We did not have the opportunity to explore further medical device-related pressure ulcer reporting in other care settings.

5. Conclusions

This qualitative study explored determinants of practice for reporting medical device-related pressure ulcers. These factors relate to individuals, their social environment, healthcare organisations, and the broader healthcare system. Consistent with the wider body of research in incident reporting, our findings show that education, openness, and teamwork are the main facilitators for reporting. The negative impact on the process was the perception of consequences, knowledge and attitudes, peer influence, financial disincentives, workload, time, and staffing. Interestingly, we found that device procurement may promote or hinder the reporting process. The identified determinants of practice can support future implementation of reporting guidelines and processes aiming to improve clinicians' reporting behaviour. Strategies implemented in the broader context may need tailoring and refining to meet the need for improvement in medical device-related pressure ulcer reporting. This, in turn, may improve nursing care quality and safety and facilitate the improvement and development of safer medical devices.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104326.

Data sharing statement

Participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Funding

One of the co-authors was partly funded by the EPSRC-NIHR Medical Device and Vulnerable Skin NetworkPLUS (EP/N02723X/1).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge all those who participated in and supported this research study.

References

1. Apold, J., Rydrych, D., 2012. Preventing device-related pressure ulcers: using data to guide statewide change. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 27 (1), 28–34.

2. Asgarian, A., Mahjour, P., Heidari, H., Khademi, N., Ghassami, K., Mohammadbeigi, A., 2021. Barriers and facilities in reporting medical errors: a systematic review study. Adv. Hum. Biol 11 (1), 17–25.

3. Atwal, A., Phillip, M., Moorley, C., 2020. Senior nurses’ perceptions of junior nurses’ incident reporting: a qualitative study. J. Nurs. Manag. 28 (6), 1215–1222.

4. Bader, D.L., Worsley, P.R., Gefen, A., 2019. Bioengineering considerations in the prevention of medical device-related pressure ulcers. Clin. Biomech. 67, 70–77.

5. Barakat-Johnson, M., Barnett, C., Wand, T., White, K., 2017. Medical device-related pressure injuries: an exploratory descriptive study in an acute tertiary hospital in Australia. J. Tissue Viability 26 (4), 246–253.

6. Barakat-Johnson, M., Lai, M., Barnett, C., Wand, T., Wolak, D.L., Chan, C., Leong, T., White, K., 2018. Hospital-acquired pressure injuries: are they accurately reported? A prospective descriptive study in a large tertiary hospital in Australia. J. Tissue Viability 27 (4), 203–210.

7. Beeckman, D., Schoonhoven, L., Fletcher, J., Furtado, K., Gunningberg, L., Heyman, H., Lindholm, C., Paquay, L., Verdú, J., Deflfloor, T., 2007. EPUAP classifification system for pressure ulcers: european reliability study. J. Adv. Nurs. 60 (6), 682–691.

8. Behnammoghadam, M., Fereidouni, Z., Keshavarz, Ra.d.M., Jahanfar, A., Rafifiei, H., Kalal, N.,2020. Nursing students’ attitudes toward the medical device-related pressure ulcer in Iran. Chronic Wound Care Manag. Res. 7, 37–42.

9. Bennett, G., Dealey, C., Posnett, J., 2004. The cost of pressure ulcers in the UK. Age Ageing 33 (3), 230–235.

10. Black, J.M., Cuddigan, J.E., Walko, M.A., Didier, L.A., Lander, M.J., Kelpe, M.R., 2010. Medical device related pressure ulcers in hospitalized patients. Int. Wound J. 7 (5), 358–365.

11. Braun, V., Clarke, V., 2021. Thematic Analysis. SAGE Publications, London.

12. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS], 2019. Hospital-acquired Conditions. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ HospitalAcqCond/Hospital Acquired_Conditions. (Accessed 1 December 2021).

13. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS], 2021. Accreditation of medicare certified providers & suppliers. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Accreditation-of-Medicare Certified-Providers-and-Suppliers Accessed: 12 January 2021

14. Charmaz, K., 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. SAGE, Los Angeles; London.

15. Chavez, M.A., Duffy, A., Rugs, D., Cowan, L., Davis, A., Morgan, S., Powell-Cope, G., 2019. Pressure injury documentation practices in the Department of Veteran Affairs: a quality improvement project. J. Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 46 (1), 18–24.

16. Clay, P., Cruz, C., Ayotte, K., Jones, J., Fowler, S.B., 2018. Device related pressure ulcers pre and post identification and intervention. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 41, 77–79. Coleman, S., Smith, I.L., Nixon, J., Wilson, L., Brown, S., 2016. Pressure ulcer and wounds reporting in NHS hospitals in England part 2: survey of monitoring systems. J. Tissue Viability 25 (1), 16–25.

17. Crunden, E.A., Schoonhoven, L., Coleman, S.B., Worsley, P.R., 2021. Reporting of pressure ulcers and medical device related pressure ulcers in policy and practice: a narrative literature review. J. Tissue Viability 31 (1), 119–129.

18. Defloor, T., Schoonhoven, L., Katrien, V., Weststrate, J., Myny, D., 2006. Reliability of the european pressure ulcer advisory panel classification system. J. Adv. Nurs. 54 (2), 189–198.

19. NPIAP, E.P.U.A.P., PPPIA, 2019. In: Haesler, Emily (Ed.), Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline. The International Guideline.EPUAP, NPIAP, PPPIA

20. Essex, H.N., Clark, M., Sims, J., Warriner, A., Cullum, N., 2009. Health-related quality of life in hospital inpatients with pressure ulceration: assessment using generic healthrelated quality of life measures. Wound Repair Regen. 17 (6), 797–805.

21. Evans, S.M., Berry, J.G., Smith, B.J., Esterman, A., Selim, P., O'Shaughnessy, J., DeWit, M., 2006. Attitudes and barriers to incident reporting: a collaborative hospital study. Qual. Saf. Health Care 15 (1), 39–43.

22. Fletcher, J., Hall, J., 2018. New guidance on how to defifine and measure pressure ulcers. Nurs. Times 114 (10), 41–44.

23. Flottorp, S.A., Oxman, A.D., Krause, J., Musila, N.R., Wensing, M., Godycki-Cwirko, M., Baker, R., Eccles, M.P., 2013. A checklist for identifying determinants of practice: a systematic review and synthesis of frameworks and taxonomies of factors that prevent or enable improvements in healthcare professional practice. Implement. Sci. 8 (1), 35.

24. Francis, R., 2013. Final report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. Podiatry Now 16 (4) pp. 9-9.

25. Galhardo, V.A.C., Magalhaes, M.G., Blanes, L., Juliano, Y., Ferreira, L.M., 2010. Healthrelated quality of life and depression in older patients with pressure ulcers. Wounds 22 (1), 20–26.

26. Gefen, A., Alves, P., Ciprandi, G., Coyer, F., Milne, C.T., Ousey, K., Ohura, N., Waters, N., Worsley, P., Black, J., Barakat-Johnson, M., Beeckman, D., Fletcher, J., Kirkland-Kyhn, H., Lahmann, N.A., Moore, Z., Payan, Y., Schlüer, A.-B., 2020. Device-related pressure ulcers: SECURE prevention. J. Wound Care 29 (Sup2a), S1–S52.

27. Gefen, A., Alves, P., Ciprandi, G., Coyer, F., Milne, C.T., Ousey, K., Ohura, N., Waters, N., Worsley, P., Black, J., Barakat-Johnson, M., Beeckman, D., Fletcher, J., Kirkland-Kyhn, H., Lahmann, N.A., Moore, Z., Payan, Y., Schlüer, A.-B., 2022. Device-related pressure ulcers: SECURE prevention. Second edition. J. Wound Care 31 (Sup3a), S1–S72.

28. GMC, NMC, 2015. Openness and Honesty When Things Go Wrong: The Professional Duty of Candour: General Medical Council and Nursing and Midwifery Council. Available at. https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/candour—openness-and-honesty-when-things-go-wrong. (Accessed 25 October 2021).

29. Gorecki, C., Nixon, J., Madill, A., Firth, J., Brown, J.M., 2012. What influences the impact of pressure ulcers on health-related quality of life? A qualitative patient-focused exploration of contributory factors. J. Tissue Viability 21 (1), 3–12.

30. Guest, J.F., Fuller, G.W., Vowden, P., Vowden, K.R., 2018. Cohort study evaluating pressure ulcer management in clinical practice in the UK following initial presentation in the community: costs and outcomes. BMJ Open 8 (7), e021769.

31. Ham, W.H.W., Schoonhoven, L., Schuurmans, M.J., Leenen, L.P.H., 2017. Pressure ulcers in trauma patients with suspected spine injury: a prospective cohort study with emphasis on device-related pressure ulcers. Int. Wound J. 14 (1), 104–111.

32. Health and Safety Executive, n.d.Health and Safety Executive (n.d.) Accidents and Investigations. Available at: https://www.hse.gov.uk/toolbox/managing/accidents.htm (Accessed: 28 October 2021).

33. Health Quality Ontario, 2017. Patient safety learning systems: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Ont. Health Technol. Assess. Ser. 17 (3), 1–23.

34. Jackson, D., Sarki, A.M., Betteridge, R., Brooke, J., 2019. Medical device-related pressure ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 92, 109–120.

35. Jewett, C., de Marco, H., 2019. Hidden FDA reports detail harm caused by scores of medical devices: keiser health news. Available at: https://khn.org/news/hidden-fda-database

36. Kalisch, B.J., 2006. Missed nursing care: a qualitative study. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 21 (4), 306–313 quiz 314–5. medical-device-injuries-malfunctions/ Accessed: 21 July 2020.

37. Kline, M., Seabold, K., McNett, M., 2020. Chapter four - financial data in hospitals and health systems. In: McNett, M. (Ed.), Data for Nurses. Academic Press, pp. 47–57.

38. Padula, W.V., Delarmente, B.A., 2019. The national cost of hospital-acquired pressure injuries in the United States. Int. Wound J. 16 (3), 634–640.

39. Pfeiffer, Y., Manser, T., Wehner, T., 2010. Conceptualising barriers to incident reporting: a psychological framework. Qual. Saf. Health Care 19 (6), e60.

40. Polit, D., Beck, C., 2017. Nursing research. Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice, 10th edn Wolters Kluwer.

41. Rashed, A., Hamdan, M., 2019. Physicians' and nurses' perceptions of and attitudes toward incident reporting in Palestinian hospitals. J. Patient Saf 15 (3), 212–217.

42. Samuriwo, R., 2012. Pressure ulcer prevention: the role of the multidisciplinary team. Br. J. Nurs. 21 (5) pp. S4, S6, S8 passim.

43. Shahin, E.S., Dassen, T., Halfens, R.J., 2009. Pressure ulcer prevention in intensive care patients: guidelines and practice. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 15 (2), 370–374.

44. Smith, I.L., Nixon, J., Brown, S., Wilson, L., Coleman, S., 2016. Pressure ulcer and wounds reporting in NHS hospitals in England part 1: audit of monitoring systems. J. Tissue Viability 25 (1), 3–15.

45. Squitieri, L., Waxman, D.A., Mangione, C.M., Saliba, D., Ko, C.Y., Needleman, J., Ganz, D.A., 2018. Evaluation of the Present-on-Admission Indicator among Hospitalized Feefor-Service Medicare Patients with a Pressure Ulcer Diagnosis: Coding Patterns and Impact on Hospital-Acquired Pressure Ulcer Rates. Health Serv Res 53 (Suppl. 1), 2970–2987 Suppl Suppl 1.

46. Tan, J.J.M., Cheng, M.T.M., Hassan, N.B., He, H., Wang, W., 2020. Nurses' perception and experiences towards medical device-related pressure injuries: a qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 29 (13–14), 2455–2465.

47. Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., Craig, J., 2007. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 19 (6), 349–357.

48. Ursavaş, F.E., İşeri, Ö., 2020. Effects of education about prevention of pressure ulcer on knowledge and attitudes of nursing students. J. Tissue Viability 29 (4), 331–336.

49. Weller, C.D., Team, V., Gershenzon, E.R., Evans, S.M., McNeil, J.J., 2018. Pressure injury identification, measurement, coding, and reporting: key challenges and opportunities. Int. Wound J 15 (3), 417–423.

50. Welsh, L., 2018. Wound care evidence, knowledge and education amongst nurses: a semisystematic literature review. Int. Wound J. 15 (1), 53–61.

51. Who, 2003. Medical device regulations: global overview and guiding principles. Available at: World Health Organisation, Switzerland, Geneva. https://www.who.int/medical_ devices/publications/en/MD_Regulations.pdf.

52. Who, 2006. Bridging the “know-do” gap. WHO Press, Geneva, Switzerland.

53. Who, 2013. Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310 (20), 2191–2194.

54. Wu, A.W., McCay, L., Levinson, W., Iedema, R., Wallace, G., Boyle, D.J., McDonald, T.B.,Bismark, M.M., Kraman, S.S., Forbes, E., Conway, J.B., Gallagher, T.H., 2017. Disclosing adverse events to patients: international norms and trends. J. Patient Saf. 13 (1).

⁎ Corresponding author. E-mail address: 该Email地址已收到反垃圾邮件插件保护。要显示它您需要在浏览器中启用JavaScript。 (E.A. Crunden).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104326

0020-7489/© 2022 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

This article is excerpted from the International Journal of Nursing Studies 135 (2022) by Wound World.