It is beginning to feel — just a little, as if the world may be returning to normal and we are once again starting to focus on our business as usual activities — improving the quality of care for patients with or at risk of wounds.

I have been reflecting on the importance of standardising care and following best practice and it seems there is a growing number of pathways put forward to help achieve both of these, but as I reviewed the existing pathways it became very clear to me that they differ in how they view the patient journey.

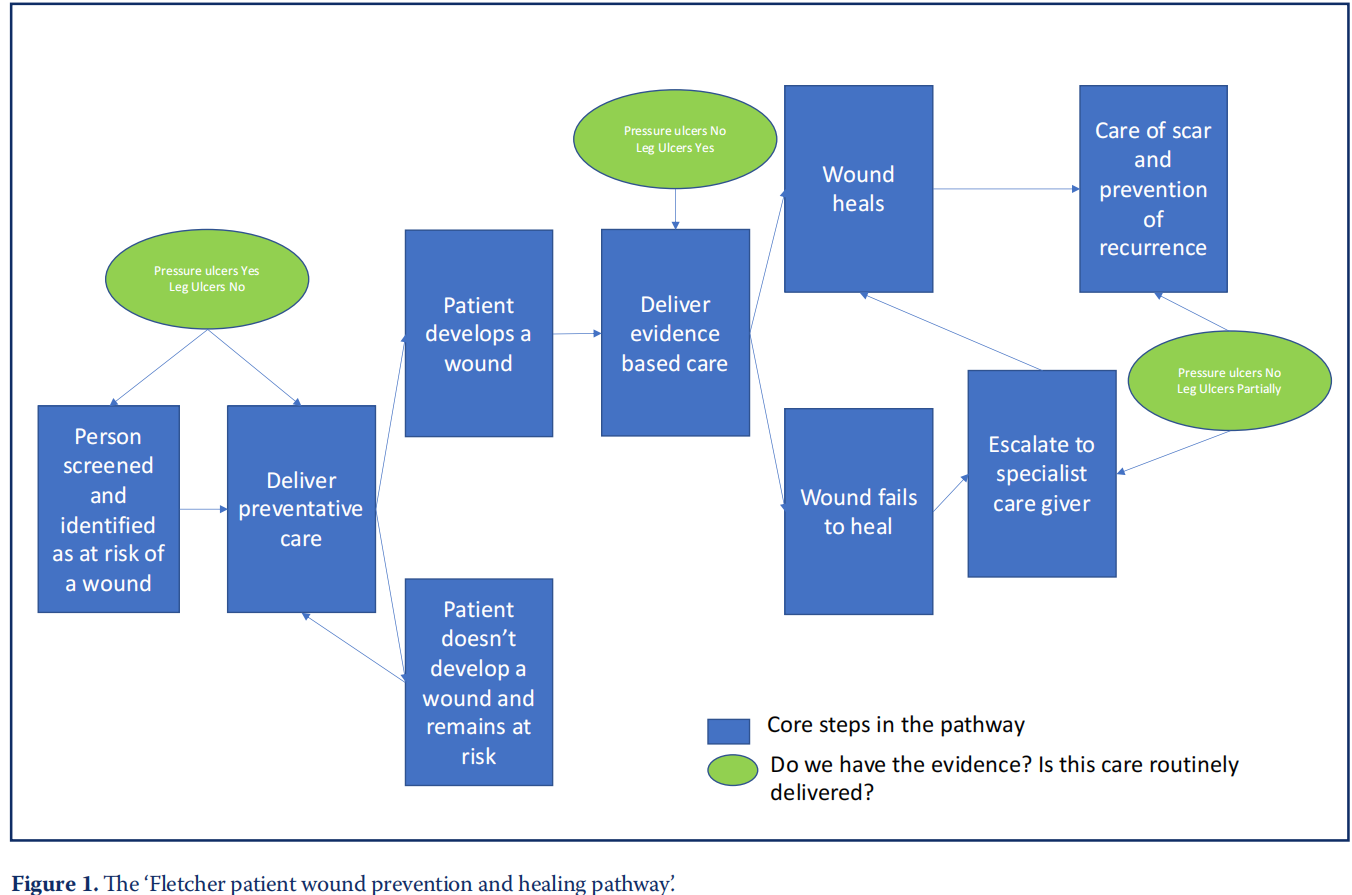

The most interesting point for me was that start point seems to be completely different depending on the aetiology of the wound. In pressure ulcers (PU) the pathways start with prevention and focus on preventing the patient developing a wound. However once they do get a PU, beyond reporting and investigating, there is little guidance on how to manage the patient to optimise their healing trajectory or prevent recurrence. Indeed there is little in the literature about either of these aspects of PU care. If you look at leg ulcer pathways, they tend to start when the patient has a wound, aiming to improve the healing rate/process, and sometimes extending beyond to prevention of recurrence.

Why don’t they all start in the same place? It would seem to make more sense if they all started with primary prevention, covered healing and also secondary prevention, but they don’t. This perhaps also explains why prevalence and costings for different aetiologies varies so widely, perhaps there are fewer PUs that cost less (in total), because we focus on preventing them, and there are more lower limb wounds because we don’t focus on preventing them, but on healing them because we have good research evidence of what to do, we just know that the evidence is not applied consistently therefore outcomes vary.

The focus of PU work has always been almost exclusively on prevention, and, that this has been beneficial is reflected in the significant reduction in PU over the last 20 years. Prevalence data from the late 1990 early 2000s suggested that almost 20% of hospital in patients (1:5) had PUs (O’Dea, 1995). We can confidently say that the percentage is now around 8–9% so less than 1:10 patients (Smith et al, 2016; Stephenson et al, 2021) a significant reduction that we should perhaps celebrate more. We also see that in the Guest data, the number and cost of PU is significantly lower than that for lower limb wounds (Guest et al, 2020).

The Guest data is, in a way, fundamentally flawed in that it only shows the cost of our failures — those that develop PUs or leg ulcers, not the cost of the work that has gone into prevention. Identifying workload and cost associated with a negative (i.e. it didn’t happen) outcome such as prevention is incredibly challenging hence some of the difficulties in securing funding for primary prevention in lower limb disease. But it must be acknowledged that the cost of treatment of PU is higher than it should be as we have not focussed on healing the PU that do occur and while we accept that some are inevitable — we need to address this. The Guest data clearly show for both PU and lower limb ulcers there is a significant cost saving where the wounds are healed quickly. But it is clear for PUs that the focus on prevention has worked in reducing the burden of disease.

For the lower limb the focus has always been on healing, the pathway is straightforward and the metrics clear (unlike in the treatment and healing of PUs). However, the numbers of patients affected (and therefore the costs) are staggeringly high. But it is clear that there is a potential to change this, we know the risk factors for venous disease, but we have no well implemented programme of risk assessment and prevention — hence the high number of ‘failures’ — or patients developing leg ulcers. While there are still problems about the consistency of care in leg ulcer management the fundamental difference between lower limb and PUs is our focus on disease prevention and their focus on disease management. We strive to prevent patient harm; in lower limb they manage the patient ‘harm’. We start when the patient is identified as being at risk, in leg ulcer services they start when the patient has the wound.

The use of the word harm is I think fundamental to the discussion, patients who develop PUs can and do die from their PU, patients and their families can and do sue the NHS, the same is not so true for patients with leg ulcers. It is an interesting point that we consider one preventable skin problem a patient harm but another not so.

I would love to see a focus across the whole patient pathway for patients with wounds of all aetiologies, the more wounds we prevent, the more money, resource and patient suffering we save, but we must equally ensure that when our prevention is less successful that we both heal the patient’s wound as quickly and optimally as we can and that we do what we can to prevent recurrence. Should we shift the focus so that we focus on healing PUs rather than categorising them and attributing blame? Should we start to work on preventing leg ulcers as much as healing them? We should definitely be trying to understand recurrence more across the spectrum.

Figure 1 shows my utopian dream (in blue) where every patient is screened for their risk of a wound (and this could be extended to skin tears, moisture lesions, diabetic foot ulcers etc) and there is a clear pathway for them to follow. Sadly, the green highlights the clinical realities. Even if this is applied to surgical wounds, where the risk assessment for a wound is irrelevant, the risk could be risk of complications such as dehiscence, infection, failure to heal or poor cosmetic/ functional outcomes.

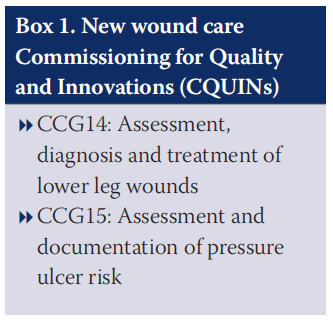

Quality improvement and incentives to improve care for patients with or at risk of wounds are once again to the forefront of a lot of clinical activity as we see the introduction of the two new Commissioning for Quality and Innovations (CQUINs) in April (Box 1). Full details of the CQUINs can be found on the NHS England website (https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/ combined-ccg-icb-and-pss-commissioning for-quality-and-innovation-cquin-indicator specification/) and supporting information including audit tools and FAQ documents for those involved in the data capture can be found on the National Wound Care Strategy website (https:// www.nationalwoundcarestrategy.net/cquin/).

For those of you that use the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) pathways as a source of reference just a reminder that they will be withdrawn shortly (NICE, undated; 2013; 2020) and the site is no longer being updated. This means that, from 1 January 2022, the content on NICE Pathways will not reflect all the latest guidance and advice. Some pathways will be removed sooner, to avoid showing out-of-date information on the site.

REFERENCES

1. Guest JF, Fuller GW, Vowden P (2020) Cohort study evaluating the burden of wounds to the UK’s National Health Service in 2017/2018: update from 2012/2013. BMJ Open 10(12):e045253. https://doi.org/10.1136/ bmjopen-2020-045253

2. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (undated) NICE Pathways. https://tinyurl.com/2p8whtrz (accessed 1 March 2022)

3. NICE (2013) Varicose veins: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline [CG168] https://tinyurl.com/2p8smsup (accessed 1 March 2022)

4. NICE (2020) Varicose veins in the legs overview – clinical pathway https:// tinyurl.com/47rpb9fh (accessed 1 March 2022)

5. O’Dea K (1995) The prevalence of pressure sores in four European countries J Wound Care 4 (4):192 –5. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.1995.4.4.192

6. Smith IL Nixon J, Wilson L, Brown S et al (2016) Pressure ulcer and wounds reporting in NHS hospitals in England part 1: Audit of monitoring systems J Tissue Viability 25(1):3–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtv.2015.11.001

7. Stephenson J, Fletcher J, Parfitt G, Ousey K (2021) National audit of pressure ulcer prevalence in England: a cross sectional study Wounds UK 17(4):45– 55. https://tinyurl.com/2p98dnts (accessed 1 March 2022)

This article is excerpted from the Wounds UK | Vol 18 | No 1 | 2022 by Wound World.