Statistics suggest that around 100 million patients in China each year need wound care with about 30 million patients suffering from skin ulcers (Fu, 2020). Wound care is an expensive burden for healthcare, it was estimated that the average cost for managing one chronic skin ulcer was 12,227 RMB Yuan in from a nationally representative sample in 17 hospitals between 2007 and 2008 (Jiang et al, 2011). On a global perspective, in 2014, the annual cost for wound care was an average of $US 2.8 billion, which was estimated to climb to $US 3.5 billion in 2021 (Sen et al, 2019). In Europe, 2–4 % of European healthcare budgets are spent on wound care alone, as one problematic wound can cost anywhere between €665 to €10000 for each patient (Gottrup et al, 2010).

Multifactorial issues such as ischaemia, risk of infection, persistent inflammation, as well as impaired healing processes that include the lack of angiogenesis, epithelial migration, and cell proliferation, reduces the probability of wound healing (Mahmoudi et al, 2020). This in turn will negatively affect the quality of life of patients and increase the cost of wound management (Mahmoudi et al, 2020). However, the most pressing problem with wound management is that wounds are in many instances not considered as an actual disease and/or speciality, meaning that patients suffering from wounds are being treated by health professionals who, rather than base wound management on evidence-based guidelines, treat these patients with care only based on their experience (Corbett 2012). This leads to a lack of understanding of the wound environment and the corresponding signals such as exudate and signs and symptoms of local infection (Mahmoudi et al, 2020). A possible answer to this issue is the creation of specialised wound care centres that would be able to address the lack of standardised evidence-based care protocols. Moreover, lack of specialised wound care education, at all levels of health professionals, is contributing to mismanagement of these patients (Mahmoudi et al, 2020).

The authors, who are active members of The Chinese Wound Management Association, strive to overcome the main challenges in wound management by promoting a multidisciplinary approach to wound care and support of evidence-based practices for better outcomes in holistic management of these patients suffering from acute and chronic wounds.

The use of local antimicrobials

The prevention and management of wound infection is central to aid the healing process. Although, not all wounds will necessitate use of systemic antibiotics, they may benefit from the use of topical antimicrobials as part of a holistic standard of care (Nakamura and Daya, 2007). Compared with systemic antibiotic therapy, topical antimicrobial application, with silver for example, has many potential advantages (Lipsky and Hoey, 2007). These types of dressings, containing an antimicrobial agent, are applied topically to the wound providing a broad spectrum of non-selective anitmicrobial action (Vowden et al, 2011).

It is important to balance antimicrobial activity against the tolerance limits of living tissue to avoid cytotoxicity when considering wound antiseptics (Daeschlein, 2013). Wound antimicrobials must provide broad‐spectrum activity, immediate onset and long lasting activity but also provide safe activity on both healthy and injured skin as well as provide good tolerance without adverse effects (Daeschlein. 2013). Topical antimicrobials are currently considered as a reasonable and practical method to reduce the risks posed by wound infection (Wounds UK, 2013).

Use of silver as a topical antimicrobial

The earliest records of use of silver for medicinal purposes go back to the Chaldeans (present day Northern Iraq) as early as 4,000 before the common era (BCE) and the Han Dynasty in China circa 1500 BCE (Ebrahiminezhad et al, 2016; Sim et al, 2018). Silver based compounds were also used by Hippocrates and the Macedonians for wound-healing and wound infection prevention and treatment — they surmised that silver compounds not only had the capacity to prevent infections but also promote the healing process. Silver colloids, complexes of silver and proteins known as mild silver protein were then used in the early 20th century for antimicrobial therapy and regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the 1940’s in various forms including solutions, ointments, colloids and foils (Ebrahiminezhad et al, 2016). The increasing problem of antibiotic resistance has made health professionals look back at the use of different antimicrobials, in 1968 Fox published the benefits of use of silver sulfadiazine (SSD) in burn wounds. However, SSD cream has been shown to have a relatively short action necessitating frequent dressing changes within 12 to 24 hours and its penetration of eschar is poor (Gupta et al, 2017). Moreover, it creates a pseudo-eschar around the wound which can cause microbial colonisation around the outer edges, it was also observed in studies to be ineffective in wounds greater than 50% of the total body surface area, especially with Gramnegative bacteria. Other evidences state that SSD delays wound healing time and that there is no direct evidence of improved healing or reduction in infection (Wasiak et, 2013; Hussain and Ferguson 2006; De Garcia 2001). Silverbased wound dressings have greatly improved in efficacy in the past decades and it has been reported that dressings with sustained release of silver have better outcomes in wound healing, patients health related quality of life (HRQoL) and are more cost effective (Sim 2017; Gupta et al, 2017).

Technology Lipido-Colloid (TLC) with silver sulphate

Technology Lipido-Colloid (TLC) was developed by Laboratoires URGO (France). It comprises a matrix containing hydrocolloid and lipophilic substances. The TLC Matrix has been shown to promote fibroblast proliferation, which in turn also contributes to the formation of new tissue (Bernard et al, 2005; McGrath et al, 2014; White 2015). In contact with exudate, the hydrocolloid polymers are hydrated and bind with the lipidocolloid interface, which is designed to reduce adhesion to the wound surface (Meaume et al, 2002) allowing atraumatic removal (Meaume et al, 2004). Silver sulphate (3.5%) has been incorporated with the TLC healing matrix to provide antimicrobial properties and is indicated for the management of acute wounds and hard-to-heal wounds at risk of or showing signs of infection (White et al, 2015). In vitro studies concluded that from the first hours and throughout the duration of the study (7 days), the reduction in the number of colony forming units (CFU) for all the bacterial strains studied was more than 105 , concluding that the TLC-Ag contact layer demonstrates antibacterial efficacy on the microorganisms tested (White et al, 2015). Clinical evidence includes a multicentre, phase III, controlled, randomised trial in 24 investigating centres, conducted in two parallel groups where the first cohort was treated with the TLC-Ag interface dressing for four weeks followed by the neutral TLC dressing until the 8th week of treatment, while, the second control cohort was treated with the neutral TLC dressing throughout the eight week follow-up period (Lazareth et al, 2012). At the end of the first four weeks of treatment, the surface area of the wounds (median value) had decreased by 4.2 cm² in the TLC-Ag group versus 1.1 cm² in the control (neutral TLC group) group (p=0.0223). From week four of treatment, after replacement of the TLC-Ag dressing by the neutral TLC dressing, the reduction in surface area continued in the group previously treated with the TLC-Ag dressing, in contrast with that observed in the neutral TLC group. At the end of follow-up, the wound surface area (median value) had decreased by 5.9 cm² in the sequential group versus 0.8 cm² in the control group (p=0.002). At the end of the eight weeks of treatment, the relative surface area reduction of the wounds (median value) was significantly greater in the TLC-Ag sequential group: 47.9% versus 5.6% in the neutral TLC group (p=0.036). The clinical score for wound colonisation (defined by the presence of clinical signs among five pre-specified signs at baseline) was significantly lower in the TLC-Ag group than in the neutral TLC group (1.43 versus 2.31, respectively (p=0.0001), while the number of patients presenting a surface area reduction of greater than or equal to 40% of the initial surface area was higher in the sequential TLC-Ag group: 54.9% of wounds versus 35.4% in the neutral TLC group (P=0.051), very close to the significant level.

The following case reports demonstrate the use of a multidisciplinary approach to wound care, in China. All the patients included have given informed consent to the use of there data and images for publication.

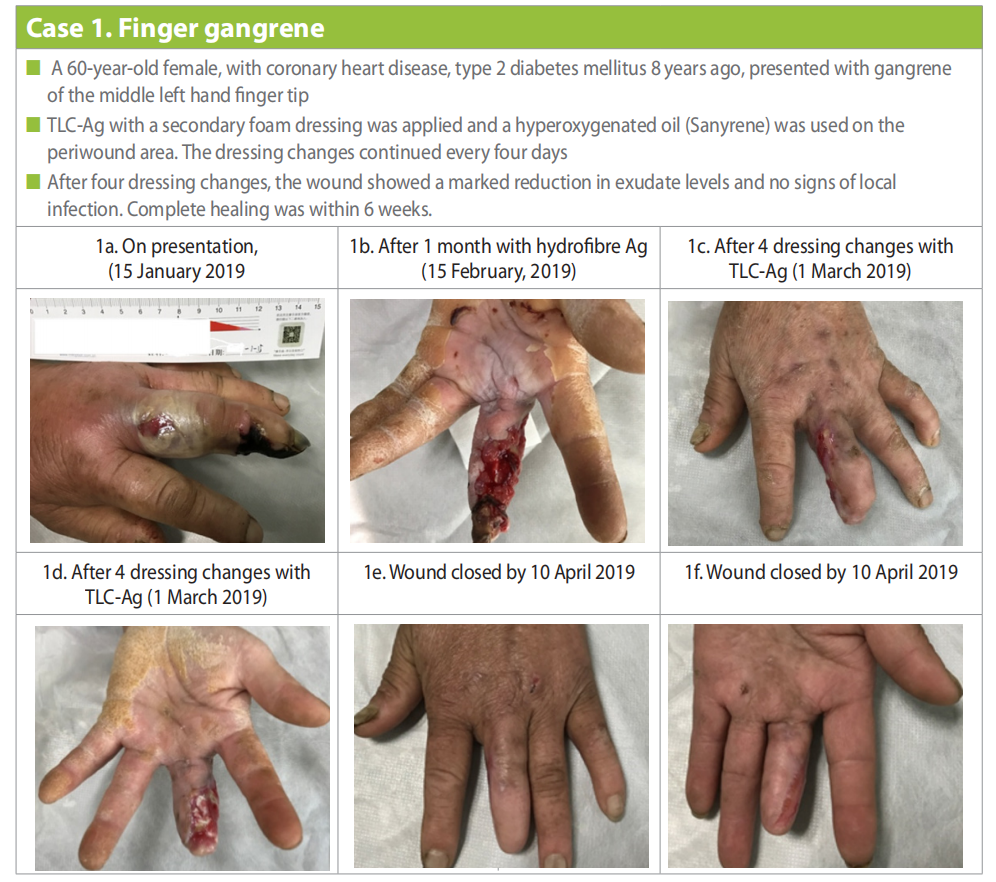

Case 1 Gu Yingtao: finger gangrene

A 60-year-old female, retired labourer, with a history of coronary heart disease and diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus 8 years ago, presented with gangrene of the middle left hand finger tip. She had redness, swelling, subcutaneous pus and an open wound at the base of the finger (Case 1a). The patient looked pale and in pain. Blood results showed low haemoglobin (95g/l), high leukocyte (12.21x109 /l), and high fasting blood glucose (9.57mmol/l). The patient was also febrile.

Furthermore, on discussion with the patient, it was identified that she had a lack of knowledge regarding diabetes, was following an unbalanced diet, and was lacking in personal hygiene. It was evident that this case should not only include management of the wound but involve the multidisciplinary team to manage the multifactorial personal and social issues.

Small incisions were made to drain the exudate of the abscess cavity, ensuring smooth drainage. The patient was started on intravenous antibiotics. On the second day, drainage from the excisions was high and malodorous, but the redness and swelling were reduced, wrinkles appear, and the patient was no longer febrile.

Hydrofibre Ag dressings were used with changes every two to three days, after one month the wound was still malodorous with high exudate levels and signs of local infection (Fig 1b). At this point a decision was made to amputate the gangrenous tip of the finger. TLC-Ag with a secondary foam dressing was applied and a hyperoxygenated oil (Sanyrene) was applied on the periwound area. The TLC-Ag dressing changes continued every four days, and after four dressing changes, the wound showed progress with a marked reduction in exudate levels and no signs of local infection (Case 1c and 1d).

Dressing changes continued using the same regime, but the management also focused on the other underlying problems. The patient was referred to the Endocrinology department where she was started on oral anti-hyperglycaemics and the patient and family were provided education on diabetes management and how to control her blood glucose level. She was also referred to the Nutrition Department for guidance regarding how to follow a balanced diet. Early passive finger exercises were also introduced to prevent stiffness. Education was also provided regarding the importance of personal hygiene to avoid skin complications. With this multidisciplinary approach to treat and manage the patient holistically, the wound was finally healed by 10 April (Case 1e and 1f ).

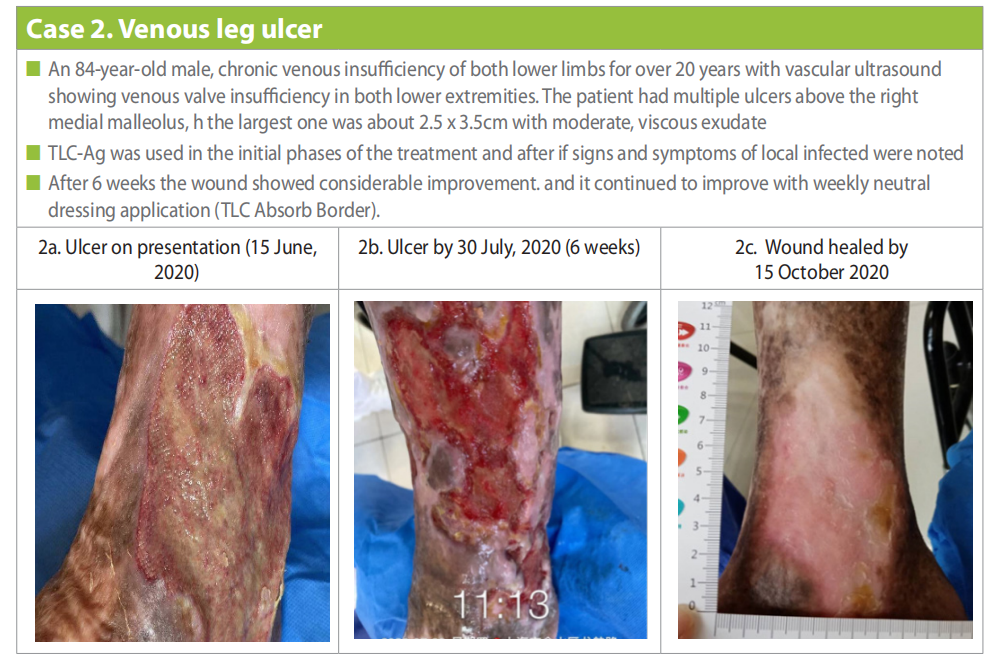

Case 2: Cai Yunmin, venous leg ulcer

An 84-year-old male, retired labourer with chronic venous insufficiency of both lower limbs for more than 20 years with vascular ultrasound showing venous valve insufficiency in both lower extremities. In 1996, he underwent double calf perforating vein ligation, superficial vein ligation, and ulcer skin grafting. He also had a history of hypertension for over 20 years and sinus bradycardia for more than 10 years.

Patient presented with multiple ulcers above the right medial malleolus, among which the largest one was about 2.5 x 3.5cm with moderate, viscous exudate (Case 2a).

The wound was flushed with normal saline (0.9%) and local debridement was done. TLC-Ag dressing was applied as the primary dressing, this was covered by a secondary dressing of gauze and compression (traditional 4 layer compression was used throughout) was applied to the lower limb. The dressing was changed daily for 2 weeks. Thereafter, the dressing changes were extended to three times per week with local application of TLC-Ag dressing, a secondary foam dressing and compression. By the 30 July the ulcer showed signs of progress with a healthier wound bed (Case 2b). After the 8-week outpatient dressing change, the patient was instructed to change the dressing in the outpatient clinic once a week and perform the other two changes at home by himself. At this point, a neutral foam dressing was applied (UrgoTul [TLC] Absorb Border) and the TLC Ag dressing was only applied if signs of local infection were visible. Compression therapy was continued throughout the treatment. The wound was completely healed by 15 October (Case 2c).

During the wound management regimes, the patient was also managed holistically to manage his overall condition by control hypertension, antihypertensive drugs were prescribed. Diet coaching was also provided to control/ prevent overweight.

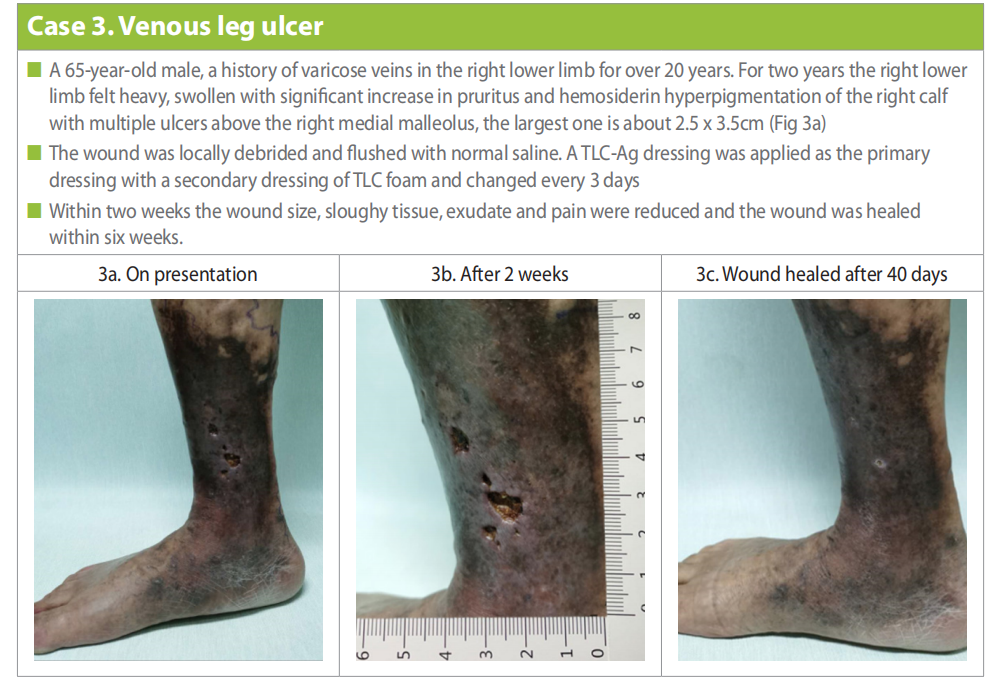

Case 3 Zhao Yongfeng: venous leg ulcer

A 65-year-old male, retired labourer, with a history of varicose veins in the right lower limb for over 20 years. In the past two years the right lower limb felt heavy, swollen with significant increase in pruritus and hemosiderin hyperpigmentation of the right calf and multiple ulcers above the right medial malleolus, among which the largest one (on presentation) is about 2.5 x 3.5cm (Case 3a). History of trauma to the right lower limb and exposure to cold water was also noted.

Ultrasound showed widened inner diameter at the right side of the saphenofemoral junction and venous valve insufficiency (severe). Other findings included widened inner diameter of the great saphenous vein trunk on the right and venous valve insufficiency (severe). The ultrasound also revealed widened inner diameter of the perforating vein between the dilated superficial vein and the posterior tibial vein at 5cm above the medial malleolus and valve insufficiency (severe). Radiofrequency endovenous obliteration for the great saphenous vein trunk of the affected limb and foam sclerotherapy for tributaries of the varicose veins was conducted.

The wound was locally debrided and flushed with normal saline. A TLC-Ag dressing was applied as the primary dressing with a secondary dressing of TLC foam (UrogTul Absorb). Dressing changes were done every three days. Lower limb compression (traditional 4 layer and continued throughout treatment ) was also applied. Within two weeks the wound size was reduced (2.0 x 1.8cm) (Case 3b), with reduction also in sloughy tissue, exudate and pain. Compression and wound management continued and the wound was healed within six weeks (Case 3c).

The successful management was attributed to the combination of minimally invasive treatment under ultrasonic guidance and treatment a multidisciplinary approach.

Case 4 Liu Xinglong and Lang Wenhua: pyoderma gangrenosum

A 57-year-old male presented with ulcers in both legs complicated with pain for six months (Case 4a and 4b). Past medical history included 20 years of hypertension, 17 years of old myocardial infarction, 20 years of cerebral infarction and 28 years of psoriasis vulgaris. Initially, oedematous impetigo was present, which gradually ruptured and enlarged to form the ulcers with surrounding redness and swelling that gradually spread outwards. After multiple visits to other hospitals, no improvement was noted and the skin ulcers became worse and very painful. The patient self-referred to the dermatology department of the hospital on 22 June 2019. He was admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum and a consultation was sent to the wound treatment centre. Prednisone and Sulfasalazine was initiated for antiinflammatory treatment and immune regulation. The dose of prednisone is 30mg per day for 15 days. After 15 days, The dose of prednisone was reduced by 5mg every 15 days and stopped using prednisone after 3 months. Sulfasalazine has antibacterial, anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects. The dose is 3g per day, divided into 3 doses and continued until the rash is fully recovered.

Colour Doppler ultrasonography of the arteries and veins of both lower extremities showed bilateral lower extremity arteriosclerosis. Other problems identified were poor unbalanced nutrition, other comorbidities that necessitated systemic management (e.g. secondary Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. The patient was admitted to the hospital with persistent trauma and a small amount of secretion covering the lesion. Considering the coexistence of bacterial infection, the discharge was taken and sent for bacterial culture and drug sensitivity test, which showed a Klebsiella pneumoniae infection.

Considering the onset of gangrenous pyoderma often associated with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease (Crohn’s disease), the patient complained of normal stools, no bloody stools, abdominal pain and other symptoms, and occasional constipation and diarrhoea. To further clarify the diagnosis, colonoscopy was performed and no significant abnormalities were seen.

Pyoderma gangrenous is often combined with lymphohematopoietic system disease. The patient had normal blood tests, no recent fever, malaise, bone and joint pain and bleeding tendency, and no indication for bone marrow aspiration, so the combination of lymphopoietic system diseases was not considered for the time being.

Pyoderma gangrenous is often combined with connective tissue disease. The patient had no recent clinical manifestations such as fever, arthritis, muscle pain, specific rash, Raynaud’s phenomenon and anaemia, so he was not considered to be combined with connective tissue disease. Furthermore, the patient was very anxious and he had limited mobility mostly due to the severe pain.

Initially the wound was flushed with normal saline and debridement was conducted. TLC-Ag dressing was applied as a primary dressing with a secondary dressing of gauze which was held in place by bandaging. Dressing was changed every two days. After three dressing changes (6 days), the wound bed looked healthier (Case 4c and 4d). By day 11, the wound was improved and the dressing regime was changed to a hydrocolloid dressing (Case 4e and 4f).

The management of the patient was conducted by a multidisciplinary team to control the dermatological disease, manage the wound and offer support regarding nutrition, health education and psychotherapy.

Case 5 Chu Weiying: lymphoedema of right calf with skin ulcer

A 62-year-old male presented on the 18 November 2019, with right calf swelling that had been present for more than two years and skin ulceration for more than one month. Patient had a long-standing history of type 2 diabetes mellitus with diabetic peripheral neuropathy and erysipelas of the right calf. He also suffered from hypertension.

Colour Doppler ultrasound for arteriovenous vessel and lymphoedema of both lower extremities showed that there was no thrombosis in the deep veins or plaques in the arteries of either of the lower extremities. However, the full-thickness subcutaneous tissue of the right calf was thickened, and a twisted and expanded network-like cavity could be seen. The lumen did not collapse when the probe was pressurised, and the thickness of the deep fascia was normal.

Multiple sloughy ulcers were present with heavy purulent exudate. The surrounding skin was red and swollen, with high skin temperature, keratinisation, and papilloma (Case 5a). Ultrasound debridement was conducted (Case 5b) and a silver alginate dressing applied, secondary dressing pad and compression with tubular elastic fabric and short stretch bandage with a figure-eight technique, avoiding pressure around the joints. Dressing was changed every two days.

Manual lymphatic drainage was performed and functional exercise that included ankle pump exercises. Education was conducted to ensure concordance with compression, this included checking of the colour and temperature of the toes that would be indicative of too tight bandaging, continue rehabilitation exercise for lymphoedema at home, balanced nutrition, quit tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption and education regarding holistic management of diabetes.

By 20 November (4 days) the swelling of the limb and sloughy wound tissue was reduced (Case 5c). Thereafter, as exudate had decreased, the primary dressing was changed to TLC Ag with dressing changes every three days. By the first dressing change (23 November), the exudate had considerably decreased in amount and viscosity and wound bed appeared healthier (Case 5d). By 30 November the wound bed continued to improve and swelling of the lower limb was greatly reduced (Case 5e). By the day 13 (31 November) the ulcers were healed and lower limb swelling was almost completely reduced (Case 5f).

The successful management involved a multidisciplinary approach to manage the patient and the wound holistically to ensure better outcomes.

Discussion

Consistent wound management and treatment provided by a multidisciplinary team has been shown in several publications to improve wound healing outcomes (Chung et al, 2015; Buggy and Moore, 2017; Mii et al, 2017; Flores et al, 2019; Joret etal, 2019). Coordination between different specialities ensures that a patient and his/her wounds are managed in a holistic manner. Moreover, the choice of appropriate wound dressings, as part of holistic, evidence-based standard of care, is imperative in order to heal wounds quickly and efficiently. Clinicians can achieve this by selecting and applying the right dressing at the right time.

The cases presented have shown that the use of the non-adherent antimicrobial dressing discussed (TLC-Ag) can provide clinicians with an evidence based solution that can help achieve better wound care outcomes in a variety of cases. Other published cases regarding the same dressing in other categories of wounds (e.g. burns) provide encouraging results for other clinicians who want to evaluate the use of this dressing.

Limitations

The care provided to the patients included in this case report is based on the positive outcomes of other studies, mainly conducted in Europe. The authors recognize that the limitation to five cases may be indicative of lack of generalisability and suggest conducting more cases in China to further determine the efficacy of this treatment.

References

1. Bernard FX, Barrault C, Juchaux F et al (2005) Stimulation of the proliferation of human dermal fibroblasts in vitro by a lipidocolloid dressing. J Wound Care14(5):215–20. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2005.14.5.26775

2. Buggy A, Moore Z (2017) The impact of the multidisciplinary team in the management of individuals with diabetic foot ulcers: a systematic review. J Wound Care 26(6):324–39. https://doi. org/10.12968/jowc.2017.26.6.324

3. Chung J, Modrall JG, Ahn C et al (2015)Multidisciplinary care improves amputation-free survival in patients with chronic critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg 61(1):162–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2014.05.101

4. Corbett LQ (2012) Wound care nursing: professional issues and opportunities. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 1(5):189–93. https://dx.doi. org/10.1089%2Fwound.2011.0329

5. Daeschlein G (2013) Antimicrobial and antiseptic strategies in wound management. Int Wound J 10 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):9–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12175

6. De Gracia CG (2001) An open study comparing topical silver sulfadiazine and topical silver sulfadiazine– cerium nitrate in the treatment of moderate and severe burns. Burns 27(1):67–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/ s0305-4179(00)00061-9

7. Ebrahiminezhad A, Raee MJ, Manafi Z et al (2016) Ancient and novel forms of silver in medicine and biomedicine. Journal of Advanced Medical Sciences and Applied Technologies ;2(1):122–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.18869/ nrip.jamsat.2.1.122

8. Flores AM, Mell MW, Dalman RL, Chandra V (2019) Benefit of multidisciplinary wound care center on the volume and outcomes of a vascular surgery practice. Journal of vascular surgery 70(5):1612–9. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jvs.2019.01.087

9. Fox CL (1968) Silver sulfadiazine—a new topical therapy for Pseudomonas in burns: therapy of Pseudomonas infection in burns. Arch Surg 96(2):184–8. https://doi.

10. Fu X (2020) Wound healing center establishment and new technology application in improving the wound healing quality in China. Burns & Trauma 1:8. https:// doi.org/10.1093/burnst/tkaa038 org/10.1001/archsurg.1968.01330200022004

11. Gottrup F, Apelqvist J, Price P. European Wound Management Association Patient Outcome G (2010) Outcomes in controlled and comparative studies on non-healing wounds: recommendations to improve the quality of evidence in wound management. J Wound Care 19(6):237–68. https://doi.org/10.12968/ jowc.2010.19.6.48471

12. Gupta S, Kumar N, Tiwari VK (2017) Silver sulfadiazine versus sustained-release silver dressings in the treatment of burns: a surprising result. Indian Journal of Burns 25(1):38–43. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ antibiotics9040181

13. Hussain S, Ferguson C (2006) Best evidence topic report. Silver sulfadiazine cream in burns. Emerg Med J 23(12):929–32. https://doi.org/10.1136/ emj.2006.043059

14. Jiang Y, Huang S, Fu X et al (2011) Epidemiology of chronic cutaneous wounds in China. Wound Repair Regen 9(2):181–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524- 475x.2010.00666.x

15. Joret MO, Osman K, Dean A et al (2019) Multidisciplinary clinics reduce treatment costs and improve patient outcomes in diabetic foot disease. J Vasc Surg 70(3):806–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2018.11.032

16. Lazareth I, Meaume S, Sigal-Grinberg ML et al (2012) Efficacy of a silver lipidocolloid dressing on heavily colonised wounds: a republished RCT. J Wound Care 21(2):96–102. https://doi.org/10.12968/ jowc.2012.21.2.96

17. Lipsky BA, Hoey C (2009) Topical antimicrobial therapy for treating chronic wounds. Clin Infect Dis 49(10):1541–9. https://doi.org/10.1086/644732

18. Mahmoudi M, Gould LJ (2020) Opportunities and challenges of the management of chronic wounds: a multidisciplinary viewpoint. Chronic Wound Care Management and Research 7:27–36. https://doi. org/10.2147/CWCMR.S260136

19. McGrath A, Newton H, Trudgian J, Greenwood M (2014) TLC dressings Made Easy. Wounds UK 10(3):1–4. https:// www.wounds-uk.com/download/resource/1326 (accessed 23 September 2021)

20. Meaume S, Senet P, Dumas R et al (2002) Urgotul: a novel non-adherent lipidocolloid dressing. Br J Nurs 11(16 Suppl):S42–50. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2002.11. sup3.10556

21. Meaume S, Teot L, Lazareth I et al (2004) The importance of pain reduction through dressing selection in routine wound management: the MAPP study. J Wound Care 13(10):409–13. https://doi.org/10.12968/ jowc.2004.13.10.27268

22. Mii S, Tanaka K, Kyuragi R et al (2017) Aggressive wound care by a multidisciplinary team improves wound healing after infrainguinal bypass in patients with critical limb ischemia. Ann Vasc Surg 41:196–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avsg.2016.09.024

23. Moore Z, Butcher G, Corbett L et al (2014) Exploring the concept of a team approach to wound care: Managing wounds as a team. J Wound Care 23 Suppl 5b:S1–S38. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2014.23.sup5b.s1

24. Nakamura Y, Daya M (2007) Use of appropriate antimicrobials in wound management. Emerg Med Clin North Am 25(1):159–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. emc.2007.01.007

25. Sen CK (2019) Human wounds and its burden: an updated compendium of estimates. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 8(2):39–48. https://doi.org/10.1089/ wound.2019.0946

26. Sim W, Barnard RT, Blaskovich MA, Ziora ZM (2018) Antimicrobial silver in medicinal and consumer applications: a patent review of the past decade (2007–2017). Antibiotics (Basel) 7(4):93. https://dx.doi.or g/10.3390%2Fantibiotics7040093

27. Vowden P, Vowden K, Carville K (2011)Antimicrobial dressings made easy. Wounds International 2011 2(1):1–6. https://tinyurl.com/hpmcvudk (accessed 23 September 2021)

28. Wasiak J, Cleland H, Campbell F, Spinks A (2013)Dressings for superficial and partial thickness burns. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013(3):CD002106. https://doi. org/10.1002/14651858.cd002106.pub4

29. White R, Cowan T, Glover D. Supporting evidence-based practice: a clinical review of TLC healing matrix.MA Healthcare Ltd, 2015

30. Wounds UK Best Practice Statement (BPS). The use of tropical antimicrobial agents in wound management. Wounds UK, 2013 (third edition). https://tinyurl. com/3eyskx26 (accessed 23 September 2021)

This article is excerpted from the Wounds Asia 2021 | Vol 4 Issue 3 by Wound World.