INTRODUCTION

A driving force behind the growth and development of telemedicine programs across the country has been the need to increase access to medical services in rural settings. Telemedicine enhances the quality of local care1 and patient satisfaction2 by allowing patients to see specialist physicians in their home communities, rather than expending time and money traveling to large urban centers.

Since the mid-1990s, the cost of technology has rapidly decreased,3 making videoconferencing affordable to more health care recipients. In 1996, the Office of Rural Health Policy conducted an interview of rural hospitals to assess their use of telemedicine.4,5 Of the 2,472 hospitals surveyed, 499 used telemedicine. Of these, a third had used videoconferencing for a variety of clinical services. In fact, cardiologic, dermatologic, and psychiatric services were used at least once by more than 30% of facilities.

In 1996, the University of California (UC) Davis Health System began a telemedicine pilot at 3 sites within its primary care network comprising urban and suburban clinics owned by the university. The use of telemedicine in the primary care network became the prototype for telemedicine applications in a variety of rural hospitals and correctional facilities, both of which have had problems with health care access.

We review the start-up experience of a telemedicine program based in a large regional health system in northern California. We reviewed 1,000 consultations to assess demographic characteristics of patients and physicians and service provision in the program. We also assessed patient and primary care physician satisfaction. In our analysis, we compared the performance, demand, and satisfaction scores of rural and urban or suburban clinics.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

The study population included 657 patients who were seen during the course of 1,000 telemedicine consultations (some were seen for follow-up). Patients were asked by their physician about receiving specialist care through a telemedicine consultation. Participation in telemedicine was voluntary for both patients and physicians. Patients could choose to see the physician in person or by telemedocine.

On the day of the appointment, after signing an informed consent agreement, patients were briefed on the nature of the telemedicine consultation, including who would be involved and the patient’s right to change the mode of care to face-to-face consultation. Patients who were younger than 18 years required the consent of a parent or legal guardian to participate in the telemedicine consultation. In cases of medical emergency—such as acute myocardial infarction or suicidal ideation—patients were referred to local medical services in lieu of telemedicine. Patient demographic information and insurance status—commercial insurance, Medicare, Medi-Cal (California’s Medicaid), or grant support—were recorded for all consultations.

PROCEDURES

Physicians desiring specialty consultation for their patients had the option of offering telemedicine rather than traditional consultations. Patients willing to be seen by a specialist by videoconference were scheduled for an appointment at the nearest telemedicine clinic affiliated with their primary care physician’s office. A medical assistant at the primary care site arranged the consultation and faxed relevant patient history and physical examination data to the UC Davis Telemedicine Program, which forwarded the information to the specialist consultant before the consultation.

Following the consultation, patients rated their satisfaction on a 1-page questionnaire containing 5-point Likert-type items (5 = excellent). Respondents rated their ability to speak freely with their consultant, their willingness to use telemedicine in the future, the competence of the staff to handle the telemedicine equipment (ability to troubleshoot technical difficulties and to optimize audio and video capabilities), the ability of the telemedicine consultation to meet their medical needs, and overall satisfaction. The patient satisfaction form was faxed to the UC Davis Telemedicine Program and stored in secured data files. All reports of these data have been tabulated in summary form.

Primary care physicians were invited to participate in the consultation and rated their satisfaction with the experience on a 5-point Likert scale. Physicians responded to questions about their ability to understand the specialist consultant, the quality of the audio and video transmission, performing physical examinations with the aid of the specialist consultant (such as using the nasolaryngoscope), and overall satisfaction. All responses were confidential.

RESULTS

Response rates

Although refusal rates were not tracked for all patient groups, a high percentage of patients were willing to use telemedicine for consultation. Even in the area of psychiatric care, where acceptance rates for telemedicine were expected to be low, 29% of patients chose telemedicine for the initial visit, whereas 35% chose telemedicine for follow-up care. These results may not be representative of all specialty clinics provided by telemedicine.

Demand for services

The first 1,000 consultations mainly included patients seen in 6 urban or suburban clinics and 2 rural clinics. The 606 (excluding 51 patients seen in correctional facilities) patients who used telemedicine in a rural or suburban location differed significantly in age (P<0.05). The rural telemedicine patients had a larger proportion of pediatric patients (17.9% vs 7.3%) than the urban or suburban group. There was not a statistically significant difference between the proportion of male and female patients seen in the rural and suburban clinics (P = 0.13). For rural and suburban or urban clinics, cancellation rates were 10.8% and 11.5%, respectively (P = 0.75).

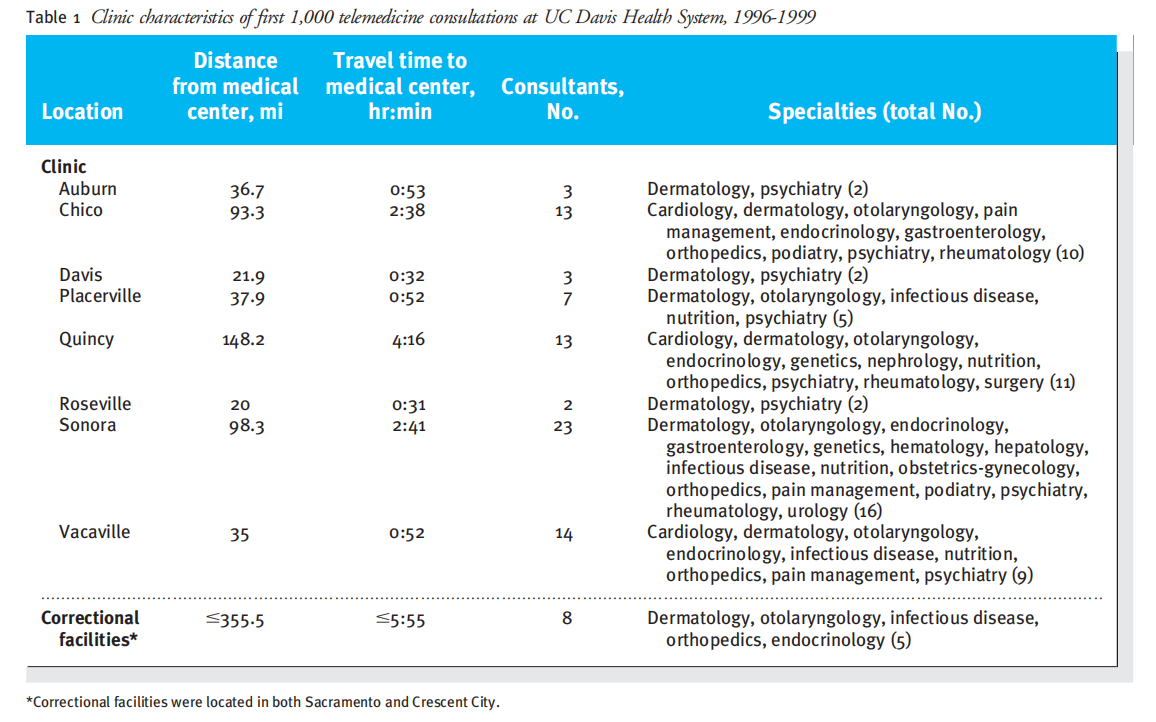

Rural and urban or suburban primary care clinics were compared in several variables using t tests (table 1). The mean distance of the rural and urban or suburban clinics was 123.25 and 40.8 miles, respectively, from UC Davis Medical Center (t = 3.55, P<0.05). Rural clinics used more consultants (18 vs 7; t = 2.38, P = 0.05) and more medical specialties for consultations (13.5 vs 5; t = 2.84, P<0.05) than urban or suburban clinics.

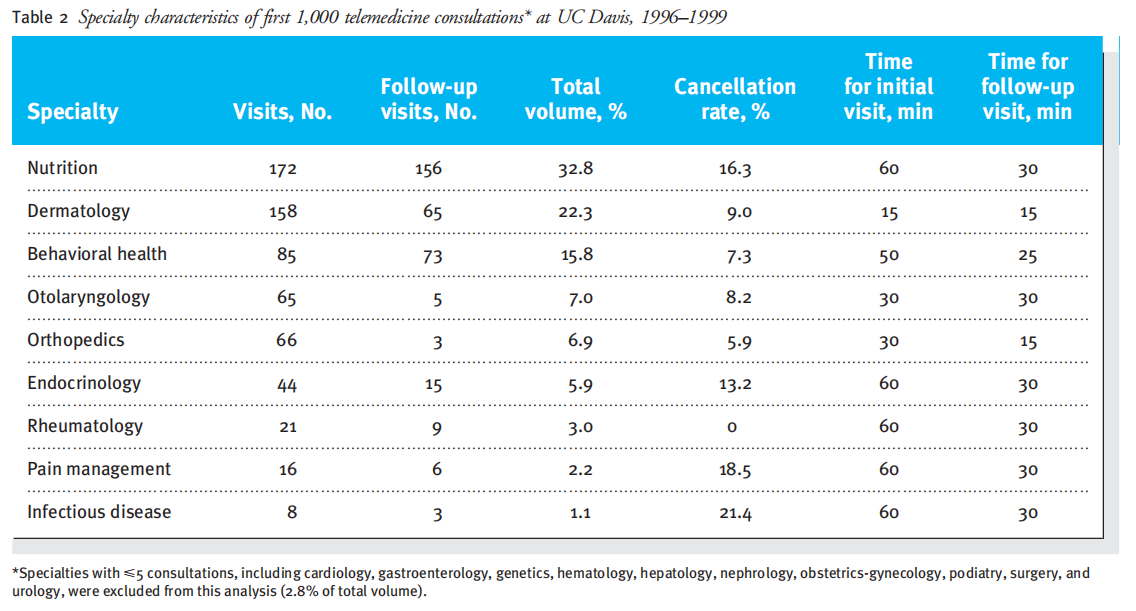

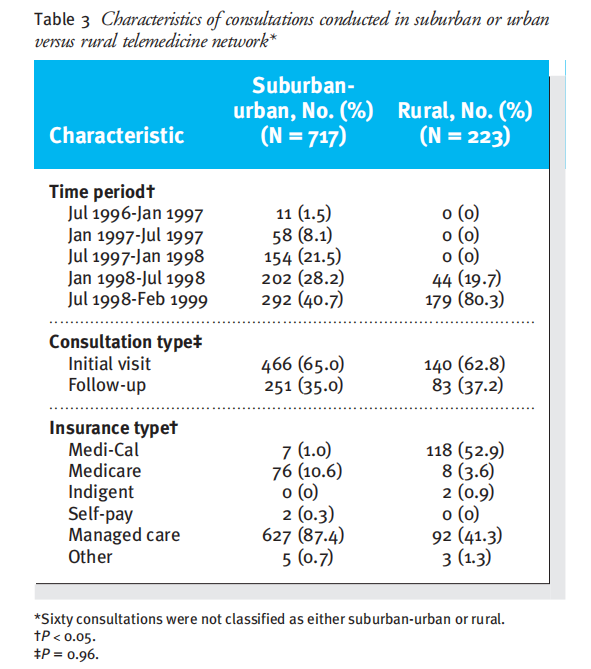

Telemedicine consultations were provided in 19 different specialty areas. Overall, the most common telemedicine consultations requested were nutrition, mainly for diabetic and lipid disorders (32.8%); dermatology (22.3%); and behavioral health, psychiatry, or both (15.8%) (table 3). Of the 1,000 consultations, 65.8% were initial evaluations and 34.1% were referrals for follow-up appointments. The overall cancellation rate was 11.1%, with a range from 21.4% (infectious diseases) to 0% (rheumatology). Specialties involving unique examination procedures or imaging techniques (otolaryngology, dermatology, and orthopedics) generally required 30 minutes or less of consultation time for initial and follow-up visits. Interview-based consultations, including those provided in nutrition, behavioral health, and endocrinology, required as much as 60 minutes for the initial evaluation and 30 minutes for follow-up appointments.

Satisfaction

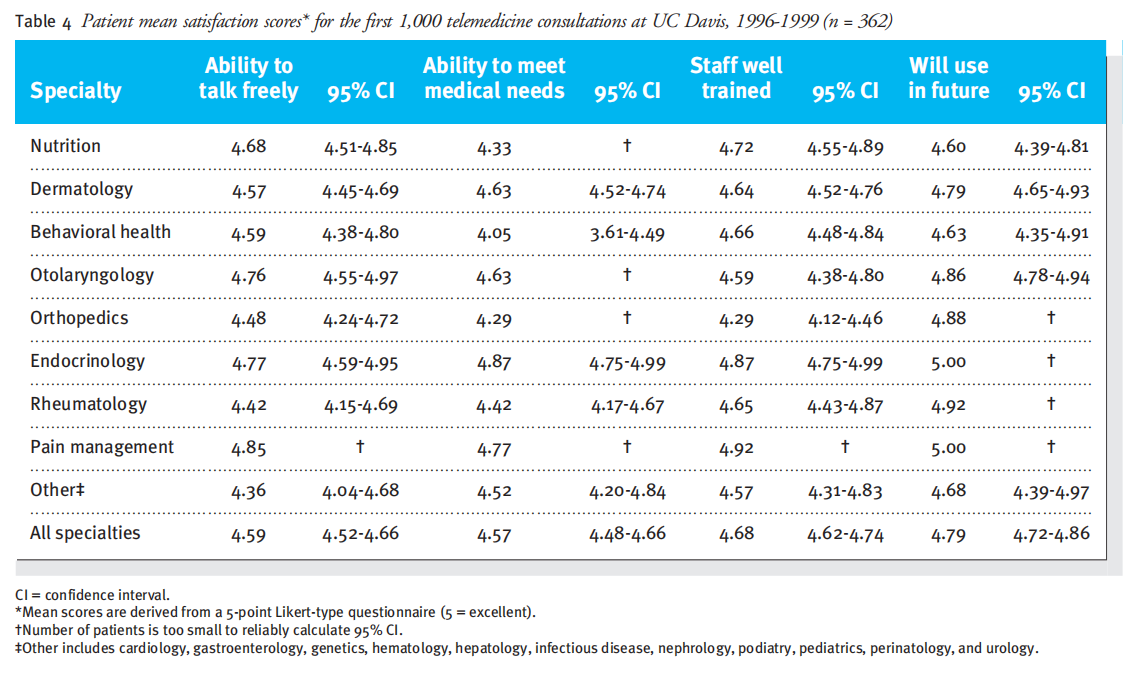

Data regarding patient satisfaction were collected on 362 of the 1,000 consultations (table 4). Interview-based specialties (such as endocrinology) were more highly rated by patients than those involving the use of scopes, cameras, or specialized examinations (such as dermatology or orthopedics).

A total of 204 primary care physicians, representing only the rural clinics, completed satisfaction surveys (table 5). Primary care physicians rated their overall satisfaction with telemedicine at 4.30 or greater. Their satisfaction with the examination process and the quality of the audio and video transmission fell below 4.00 in only 1 clinical area: rheumatology. In about 1 of 5 consultations, the physician reported a technical difficulty. Commonly reported problems were lag time between the audio and video signals, unexpected disconnections, “choppy” audio transmission, and difficulty manipulating the peripheral devices to acquire a clinically acceptable image.

Reimbursement and program costs

The method of payment was recorded for each telemedicine consultation provided (table 3). Direct costs of the services were not measured.

The type of insurance coverage showed significant differences between the rural and suburban or urban populations of telemedicine patients (P<0.05). The rural consultations were more frequently billed to Medi-Cal (52.9% vs 1.0%) and fewer consultations through commercial insurance (41.3% vs 87.4%) than the urban or suburban population. Insurance coverage through Medicare was 3 times less common in the rural population than in the urban or suburban population (3.6% vs 10.6%).

The total average cost of videoconferencing units is $12,800. Peripheral devices, such as a dermatology camera and a nasopharyngoscope, with its own light source and camera, may reach $19,000 in system costs. Variable costs for telemedicine relate to telecommunications line charges—which can be as much as $60 per hour for digital phone service connection—and clinic coordination. These costs would not be incurred in a typical face-to-face clinic.

DISCUSSION

The results from this project suggest differences in demand for specialty services between rural and suburban sites, with rural sites having higher demand overall, and in the breadth of specialties. We found high satisfaction with telemedicine consultations among both patients and primary care physicians. Participation in telemedicine was completely voluntary. Therefore, the results presented in this article may not be representative of all physicians’ and patients’ willingness to use this modality of care.

The use of telemedicine may result in increased medical interventions among the patients who use it. This is because it is being introduced to patient groups (Medi-Cal recipients) who before the availability of telemedicine had limited access to specialist services. The extent to which health service use has increased because of telemedicine cannot be stated at this time. Once data are collected on health service use resulting from telemedicine, research can be focused on changes in morbidity and mortality among telemedicine patients and possibly reducing overall health care costs.

Other concerns about telemedicine relate to the effect it may have in eroding the involvement of primary care physicians in the care of their patients. This program has found that many primary care providers, in fact, derive an educational benefit from collaborating with a physician specialist. Within our first 1,000 consultations, telemedicine referrals from primary care physicians were generated because of the limited access to medical specialists in rural communities. In the past year, this program has observed that midlevel providers—physician assistants and nurse practitioners—are increasingly referring patients to telemedicine in communities where there is a shortage of primary care physicians.

Barriers to the use of telemedicine include the problem of reimbursement. In California, a law was passed in 1996 that mandated reimbursement for telemedicine services.6 Nonetheless, many insurance payers have not developed a reimbursement policy for telemedicine and have required education about the clinical content of the standard telemedicine visit, the role of the presenting provider, and the importance of paying for the resources involved in care, mainly telecommunications costs. Medi-Cal is currently evaluating the effect of telemedicine in traditionally underserved areas and the financial effects on the state of providing payment.

At the national level, the Health Care Financing Administration has established policy mandating, as of January 1999, that Medicare reimburse for telemedicine in underserved rural areas when the referring practitioner is present. This policy, however, had little effect on the first 1,000 telemedicine consultations provided at UC Davis.

There are several limitations to the data presented in this report. First, the patients, referring physicians, consultants, and health system in this study may not be generalizable to other settings. Furthermore, diagnostic data were not collected, and there were no clinical outcome measures, only subjective ratings of satisfaction. Data on objective medical outcomes will be important to evaluate in the future because there may be diagnoses that are less amenable to treatment by telemedicine consultation. Second, the satisfaction data are limited because, owing to the lack of a telemedicine coordinator in most clinic settings,the questionnaire was not administered to every patient. In addition, there was no control group against which to compare any ratings, and the study was nonrandomized. To that end, 2 randomized controlled trials have been initiated in the past year on the delivery of home health and psychiatry through telemedicine compared with traditional face-to-face care.

Despite these limitations, these data provide important information from a usual-care perspective for those who are considering telemedicine services to provide specialty care. In the future, controlled studies are needed to further assess the effects of telemedicine on patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness.

References

1 Levine SR, Gorman M. Telestroke: the application of telemedicine for stroke. Stroke 1999;30:464-469.

2 Dick PT, Filler R, Pavan A. Participant satisfaction and comfort with multidisciplinary pediatric telemedicine consultations. J Pediatr Surg 1999;34:137-141.

3 Strode SW, Gustke S, Allen A. Technical and clinical progress in telemedicine. JAMA 1999;281:1066-1068.

4 Hassol A, Irvin C, Gaumer G, Puskin D, Mintzer C, Grigsby J. Rural applications of telemedicine. Telemed J 1997;3:215-225.

5 Hassol A, Gaumer G, Irvin C, Grigsby J, Mintzer C, Puskin D. Rural telemedicine data/image transfer methods and purposes of interactive video sessions. J Am Med Inform Assoc 1997;4:36-37.

6 Cal Bus Prof Code §2060 (amend), §2290.5; Health Saf Code§§1367&1375.1 (amend), §§1374.13&123149.5; Ins Code § 10123.85; and Welf Inst Code §14132.72 (1996).

This article is excerpted from the Original Research by Wound world.