The use of telemedicine has recently seen a sharp increase in frequency due to the ongoing global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. According to the World Health Organization, telemedicine represents “healing at a distance” [1]. They define telemedicine as “the delivery of healthcare services...by healthcare professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease and injuries.” Telemedicine has become an important and effective option for providing patient care. However, the use of telemedicine in the context of procedural therapies for pain management is new and rapidly evolving. In this commentary, we aimed to review literature and share our experience in integrating telemedicine in procedural care.

Telemedicine for Interventional Pain Care Telemedicine has been used in multiple medical fields, including procedural disciplines. It has been used as an educational tool for patients preparing to undergo vascular surgery [2] and to track postoperative complications following spinal surgery [3]. Surgeons have used telemedicine to pre-screen patients for specific surgeries, targeting remote geographic regions [4]. By incorporating detailed records, including radiographs, this method was found to be safe and effective in determining appropriateness for spine surgery.

Within the field of pain medicine, telemedicine has been used for chronic pain treatments using mobile applications and wearable technology to track symptomatology, adherence to physical activity recommendations, and follow patient progress longitudinally [5]. Telemedicine has also been used to deliver psychotherapies in efforts to alleviate chronic pain [6]. Generally, these telehealth applications are non-inferior or moderately beneficial for patient-based outcomes.

In an important innovation to improve access to chronic pain specialty care, Hanna and colleagues developed a telemedicine pain service for residents of Martha’s Vineyard [7]. A pain physician would evaluate patients presenting to a remote hospital by videoconference and, for some patients, visit the hospital to perform procedures. Of 238 initial evaluations, 121 led to on-site interventions, including 48 epidural steroid injections (ESI) and 29 medial branch blocks. Forty-nine patients were surveyed, and most responded positively to the use of this telemedicine service. Importantly, the telemedicine configuration involved a nurse present with the patient at the local hospital who performed physical exam maneuvers as part of the initial videoconference evaluation. From this study, it remains unknown whether a telemedicine evaluation of a patient at their own home would be adequate to support procedural decision making for pain interventions.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, interest in telemedicine for pain management is at an all-time high, with multiple society guidelines and expert opinions published. Shanthanna et al. recommend a conservative approach including suspension of elective in-person clinicvisits, suspension of elective pain procedures, use of telemedicine by default, and use of online self-management programs that include biopsychosocial therapeutic strategies [8]. For semi-urgent visits or procedures, they recommend maximizing the use of telemedicine wherever possible for purposes of evaluation and triage to shorten in-person time and avoid unnecessary visits. Cohen et al. also highlight CDC guidelines for prevention of viral transmission in the context of pain clinics which include hygiene techniques, facemask use, avoidance of close contact when possible, and disinfection protocols [9]. Both suggest that, due to risk of COVID-19 transmission, in-person visits should be minimized and that semiurgent procedures could be triaged using telemedicine.

Our own pain division has also published consensus opinions about the appropriateness of telemedicine for common clinical scenarios [10]. An important note is that all of these current guidelines are based on expert opinion and are within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given successes of a telemedicine pain service involving in-person evaluation of patients at a remote hospital [7], we anticipate that patients would continue to benefit from telemedicine pain care after the pandemic. Taking advantage of the unique circumstances posed by COVID-19 mitigation, we sought to examine the feasibility of performing new patient evaluations for those referred to our clinics for interventional spine procedures using a telemedicine configuration with direct communication to patients in the context of a health system with comprehensive records available in a single electronic medical record (EMR). For study feasibility, we refined our case review to patients specifically referred for ESI.

Telemedicine Evaluation Prior to Epidural Steroid Injections: The University of Pittsburgh Pandemic Experience

After obtaining approval by the Quality Improvement Review Committee of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, we conducted a descriptive case series that evaluated patients referred to two physicians (B.A. and E.H.) for consideration of ESI between 3/26/2020 and 6/19/2020 in an outpatient pain clinic setting at a large multisite single healthcare system in Western Pennsylvania (roughly 2,400 offices, 35 inpatient hospitals). Due to COVID-19 mitigation, all patients presenting to the pain clinic were initially evaluated by telemedicine; however, this was relaxed over time as safety protocols were implemented, and Pennsylvania relaxed mitigation measures. Inclusion into the case review required patients be referred specifically for ESI and seen initially by telemedicine. Exclusion criteria were referrals for general evaluation, not specifically for ESI.

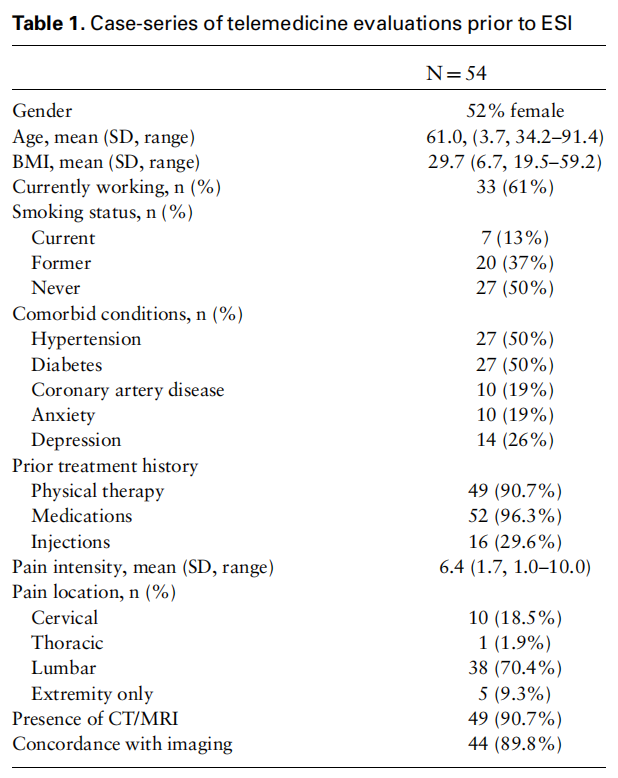

In our review of the initial telemedicine encounters,key aspects of a chronic pain evaluation were noted. Basic clinical and demographic information at the initial telemedicine visit is noted in Table 1. As determined by review of the referring providers physical exam, neurologic deficits including sensory impairments, motor weakness, or reflex changes were present in 16.7% of the cases. Most of the patients were referred by a spine surgeon (75.9%). The other 24.1% were referred by primary care physicians or orthopedic surgeons who were not spine surgeons. A referring physician encounter with a documented exam was available for review in 79.6% of patients. In the ~20% of patients that did not have a physical exam, reasons included: the referring provider also conducting a telemedicine visit (54.5%), being referred after a telephone call (27.3%), or being referred from outside the health system and not having access to those records (18.2%). During the telemedicine encounter, a limited physical exam was performed without a detailed musculoskeletal component.

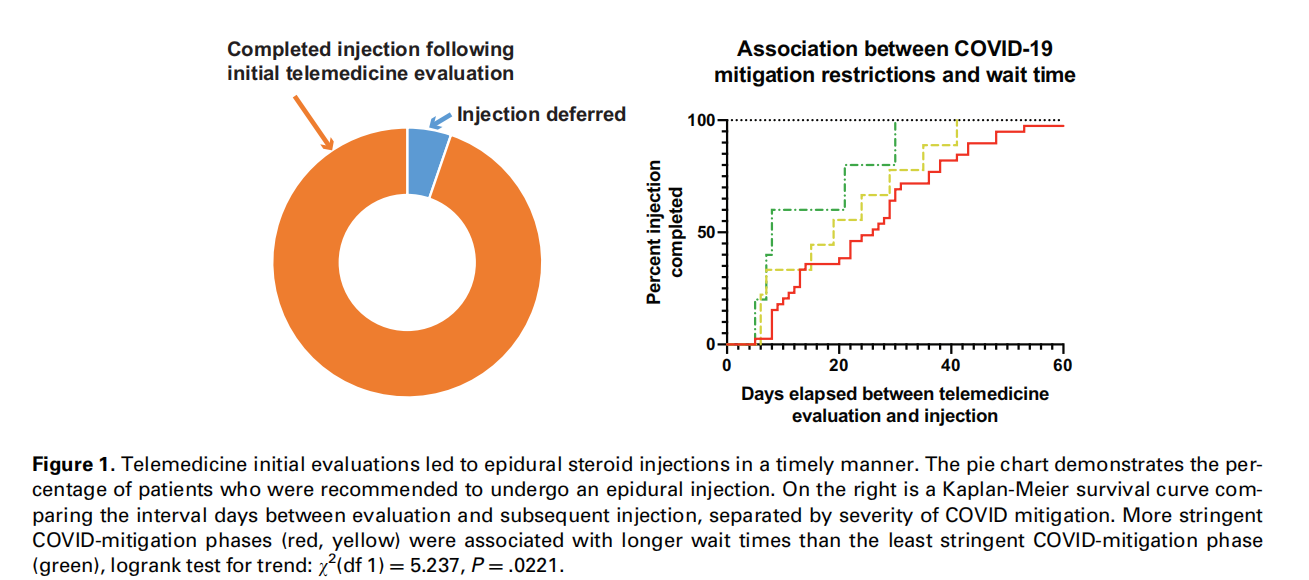

At the conclusion of the initial telemedicine evaluation, 94.4% of patients were recommended to undergo an injection procedure (Figure 1). All injections were approved by insurances. Three patients were deferred—2 for lack of advanced imaging and 1 for lack of any other prior conservative therapy. In addition to procedures, additional treatments (physical therapy, medications, and/or pain psychology) were recommended in 53.7% of patients. Of those 29 patients who were recommended additional treatments, 51.5% were in compliance at the time of their in-person procedure visit.

In the interval between the initial pain clinic telemedicine evaluation and the subsequent in-person procedure visit, there was no evidence of disease progression clinically, defined as any new neurologic signs, red flag symptoms, or ED visits related to the chief complaint. Five patients had a change in reported symptoms when comparing the referring physician’s documentation to the pain clinic’s initial telemedicine encounter. When patients arrived for their in-person procedure visits, a detailed neurologic and musculoskeletal exam was conducted to confirm that the physical exam findings were concordant with the impression from the telemedicine consultation. After this exam, only two patients had changes in the physical examination, one having improvement in motor strength and the other developing positive dural tension signs. Two patients had visits to the ED between the pain clinic visits, both for reasons unrelated to the chief complaint being addressed by the pain clinic.

Only one procedure was changed based on physical exam findings identifying a different pain generator than initially thought. That one procedure was changed from a lumbar ESI to an intra-articular hip injection based on physical examination findings localizing the pain generator to the hip. Overall 98% of in-person exam impressions were concordant with initial telemedicine consultation visit impressions.

As part of the quality improvement aspect of this project, the time interval between initial telemedicine evaluation and the in-person visit was tracked. In all patients, the time between the referral and initial telemedicine evaluation in the pain clinic ranged from 1 to 131 days with a mean of 37.6 days (median of 25 days; standard deviation 36.3 days). We found that this time interval was initially long, but decreased with the phased relaxation of COVID mitigation (Figure 1), suggesting that our approach could efficiently be incorporated into clinical practice after the COVID pandemic resolves without delays in patient care.

Conclusions

Our literature review and case-series during the COVID-19 pandemic suggest that patients who are referred for procedural care are appropriate candidates for an initial telemedicine visit. We did not identify significant progression of disease in the interval between a referring provider’s evaluation and the pain physician’s evaluation prior to ESI. Additionally, our case series suggests that a simpler, but potentially less informative, telemedicine configuration with the pain physician interacting only with the patient is adequate. Telemedicine pain services may increase access to care with good patient acceptability, potentially increasing access to non-opioid treatments in rural areas. Future work examining the safety and acceptability of these telemedicine configurations at a larger scale is needed.

References

- Ryu S. Telemedicine: Opportunities and developments in member states: Report on the second global survey on eHealth 2009 (Global Observatory for eHealth Series, Volume 2). Healthc Inform Res 2012;18(2):153–5.

- Bowers N, Eisenberg E, Montbriand J, Jaskolka J, Roche-Nagle G. Using a multimedia presentation to improve patient understanding and satisfaction with informed consent for minimally invasive vascular procedures. Surgeon 2017;15(1):7–11.

- Debono B, Bousquet P, Sabatier P, Plas JY, Lescure JP, Hamel O. Postoperative monitoring with a mobile application after ambulatory lumbar discectomy: An effective tool for spine surgeons. Eur Spine J 2016;25(11):3536–42.

- Lee S, Broderick TJ, Haynes J, Bagwell C, Doarn CR, Merrell RC. The role of low-bandwidth telemedicine in surgical prescreening. J Pediatr Surg 2003 Sep;38(9):1281–3.

- Amorim AB, Pappas E, Simic M, et al. Integrating mobile-health, health coaching, and physical activity to reduce the burden of chronic low back pain trial (IMPACT): A pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019;20(1):71.

- Rutledge T, Atkinson JH, Chircop-Rollick T, et al. Randomized controlled trial of telephone-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy versus supportive care for chronic back pain. Clin J Pain 2018;34(4):322–7.

- Hanna GM, Fishman I, Edwards DA, et al. Development and patient satisfaction of a new telemedicine service for pain management at Massachusetts General Hospital to the Island of Martha’s Vineyard. Pain Med 2016;17(9):1658–63.

- Shanthanna H, Strand NH, Provenzano DA, et al. Caring for patients with pain during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consensus recommendations from an international expert panel. Anaesthesia 2020;75(7):935–44.

- Cohen SP, Baber ZB, Buvanendran A, et al. Pain management best practices from multispecialty organizations during the COVID-19 pandemic and public health crises. Pain Med 2020; 21(7):1331–46.

10. Emerick T, Alter B, Jarquin S, et al. Telemedicine for chronic pain in the COVID-19 era and beyond. Pain Med 2020;21(9):1743–8.

This article is excerpted from the Pain Medicine, 22(12), 2021 by Wound World.