Introduction

There have been considerable advances in the implementation of telemedicine and the development of technology1–5. Telemedicine applications are continually emerging to new areas, such as surgical telementoring, emergency medicine collaboration, education of medical personnel, multidisciplinary team meetings and postoperative follow-up4,6,7. Postoperative follow-up by teleconsultation (TC) has the potential to improve care, and the technology has become user-friendly8.

Patients with a new stoma need time and support with quality of life (QoL) alterations9. Some have long and time-consuming travel to the hospital to attend follow-up consultations. TC is well suited to this patient group1. In Norway, a fibreoptic network, the Norwegian Healthcare Network, connects TC studios at district medical centres with hospitals. This network provides a high definition and safe solution, enabling high-quality telemedicine communication between primary care and hospitals.

The objective of this study was to obtain insight into the QoL of patients with a stoma, followed up in a hospital outpatient setting (controls) or by teleconsultation (intervention). Healthcare resource use, organization and patient satisfaction with the health service provided was assessed.

Methods

Patients were randomized to follow-up at the university hospital outpatient clinic (control group) or by TC (intervention group). All patients were followed up for more than 12 months after surgery. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/ show/NCT01600508).

Patients

Patients with a postsurgical stoma (ileostomy or colostomy) were candidates for inclusion in the study. All patients provided informed consent. Patients were excluded if they had a life expectancy of less than 2 years, mental illness or severe dementia, were unable to provide informed consent, or had stoma formation after palliative surgery (patients with disseminated cancer).

Ethics and consent procedure

The Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics, University of Oslo, approved the protocol (reference 2009/1432a). The Norwegian Data Inspectorate also approved the study. Patients provided written consent before entering the trial, which was performed according to the Helsinki Declaration and Good Clinical Practice.

Eligibility

All patients who had a new stoma and fulfilled the inclusion criteria were eligible for inclusion in the study. Eligibility was assessed in the immediate postoperative period. The investigators explained the nature, purpose and risks of the study to the participant, who was given an information sheet explaining the study rationale. Participants had sufficient time to read the information and consider any implications. Before signing the informed consent, any questions relating to the study were discussed.

Role of stoma nurses

Nurses with a specialization in wound and stoma care performed follow-up consultations in both trial arms. A nurse-led TC stoma and wound school was established before the clinical trial; nurses with special training in the treatment of patients with wound and stoma problems developed the curriculum. Ten nurses from TC communities all over Northern Norway were recruited. These nurses were responsible for the practical arrangements of the TC at the district medical centre (DMC). The stoma nurses were affiliated to the DMCs where the TC studios were located. Stoma nurses in both trial arms consulted gastrointestinal surgeons when necessary. Guidelines for safety monitoring were developed. Patients allocated to TC follow-up could be referred back to the university hospital at any time.

Intervention arm

Patients received a baseline consultation 0–3 months after the initial surgery. A clinical examination was performed and information about the RCT provided. When patients had provided informed consent, they were randomized by the stoma nurses. Those randomized to TC follow-up were referred to their general practitioner and the local stoma nurse at the DMC. Stoma nurses organized TC at 0–3 (defined as baseline), 6, 9 and more than 12 months. Patients could withdraw from the study and be referred back to hospital follow-up at any time.

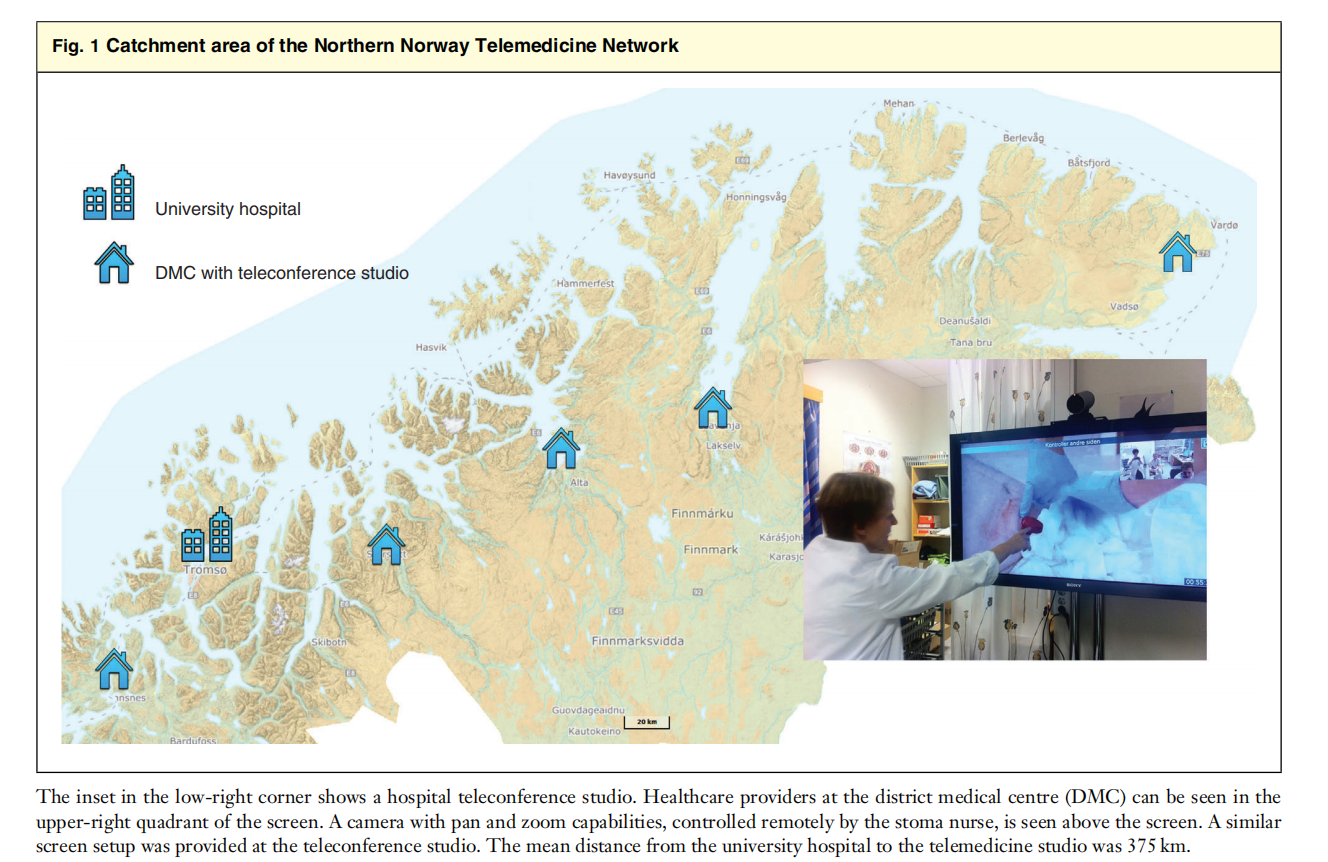

Telemedicine studios

The Cisco® TelePresence system (Cisco Systems, San Jose, California, USA) (screen at DMC: Tandberg 990MXP; screen at hospital: Tandberg 1500MXP) (Cisco Systems) and the Norwegian Healthcare Network fibreoptic cable were used for secure data transmission (Fig. 1). The telemedicine studios were located at the university hospital (Tromsø, Norway) and at the DMCs (Finnsnes, Storslett, Vadsø, Lakselv and Alta). Before the trial started, the stoma nurses received intensive training in the use and troubleshooting of the TC equipment.

Control arm

The control group consisted of patients randomized to regular stoma follow-up at the hospital’s surgical outpatient clinic. Consultants in gastrointestinal surgery or a wound and stoma nurse performed the hospital follow-up.

Randomization

Randomization was done at the baseline consultation. Once the stoma nurses had confirmed eligibility, an independent organizational unit at the University Hospital Research Department performed web-based randomization. Patients were stratified for age, sex and type of stoma (ileostomy versus colostomy). The randomization ratio was 1 : 1, and there was no block randomization or blinding of participants.

Objectives

The aim of the RCT was to compare QoL and resource use in patients with a stoma followed up by TC or in the surgical outpatient clinic. It was hypothesized that patients in the TC arm would experience moderate improvement (0⋅3–0⋅4) in QoL measured by the index score of the 3-level version of the EQ-5D™ questionnaire (EuroQol Group, Rotterdam, the Netherlands). Patient satisfaction and resource use with the telemedicine service were assessed.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

EQ-5D™ is a standardized, generic instrument for use as a measure of health outcome. Applicable to a wide range of health conditions and treatments, it provides a simple descriptive profile and a single index value for health status. The EQ-5D™ measures five dimensions of health-related QoL: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Each dimension is rated at three levels: no problems (1), some problems (2) and major problems (3)10.

Secondary outcomes

The EQ visual analogue scale (EQ-5D™-VAS) records the respondent’s self-rated health status on a vertically graduated (0–100) VAS10.

Stoma Quality-of-Life Scale

This is a 21-item questionnaire with three scales: Work/Social Function (6 items), Sexuality/Body Image (5 items) and Stoma Function (6 items)9.

OutPatient Experiences Questionnaire

The Norwegian OutPatient Experiences Questionnaire (OPEQ), evaluated by Garratt and colleagues11, is recommended for measuring patient experience in outpatient clinics12. Questions in the OPEQ relate to information on future complaints, nursing services, communication, information on examinations, contact with next-of-kin, doctor services, hospital and equipment, information on medication, and organization and general satisfaction12. Some questions were modified for a telemedicine setting.

Resource use

Resources assessed were the number of journeys to the hospital outpatient clinic, DMC, journey time, number of hospital consultations, readmissions and methods of transportation.

Follow-up schedule

Parallel follow-up programmes and patient rescheduling of preplanned appointments led to a pragmatic adjustment of the follow-up protocol. Before the trial nine appointments were planned at 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21 and 24 months, whereas after commencement of the trial four appointments were decided on, at 0–3, 6, 9 and more than 12 months.

Data gathering

A questionnaire was designed for the trial, combining all elements of the scales and questionnaires. Data were collected for patients in the intervention and control groups in identical ways. Stoma nurses received the completed questionnaires immediately after each follow-up appointment. In some instances, patients returned the completed questionnaires by mail. In the case of missing questionnaires, patients were contacted by phone. The questionnaires were optically readable, and the data were collected consecutively in a trial database. In addition to the questionnaire, demographic data were obtained from the electronic medical record and the prospective trial database.

Sample size

Sample size calculation was done according to the guidelines of Campbell et al.13 and the EQ-5D™14. Improvements in α and β were set at 0⋅05 and 0⋅2 respectively, and tests were two-sided. It was hypothesized that patients followed up by TC would have a moderate increase (0⋅3–0⋅4) in EQ-5D™ index score. As the standard deviation for patients with a stoma is not estimated for EQ-5D™, it was assumed that the standard deviation range was 0⋅18–0⋅214. To detect a moderate increase in QoL with this range, a sample size of approximately 100 patients was required. Allowing for a dropout rate of 10 per cent, 110 patients would need to be recruited. Similar estimates were calculated for the EQ-5D™-VAS.

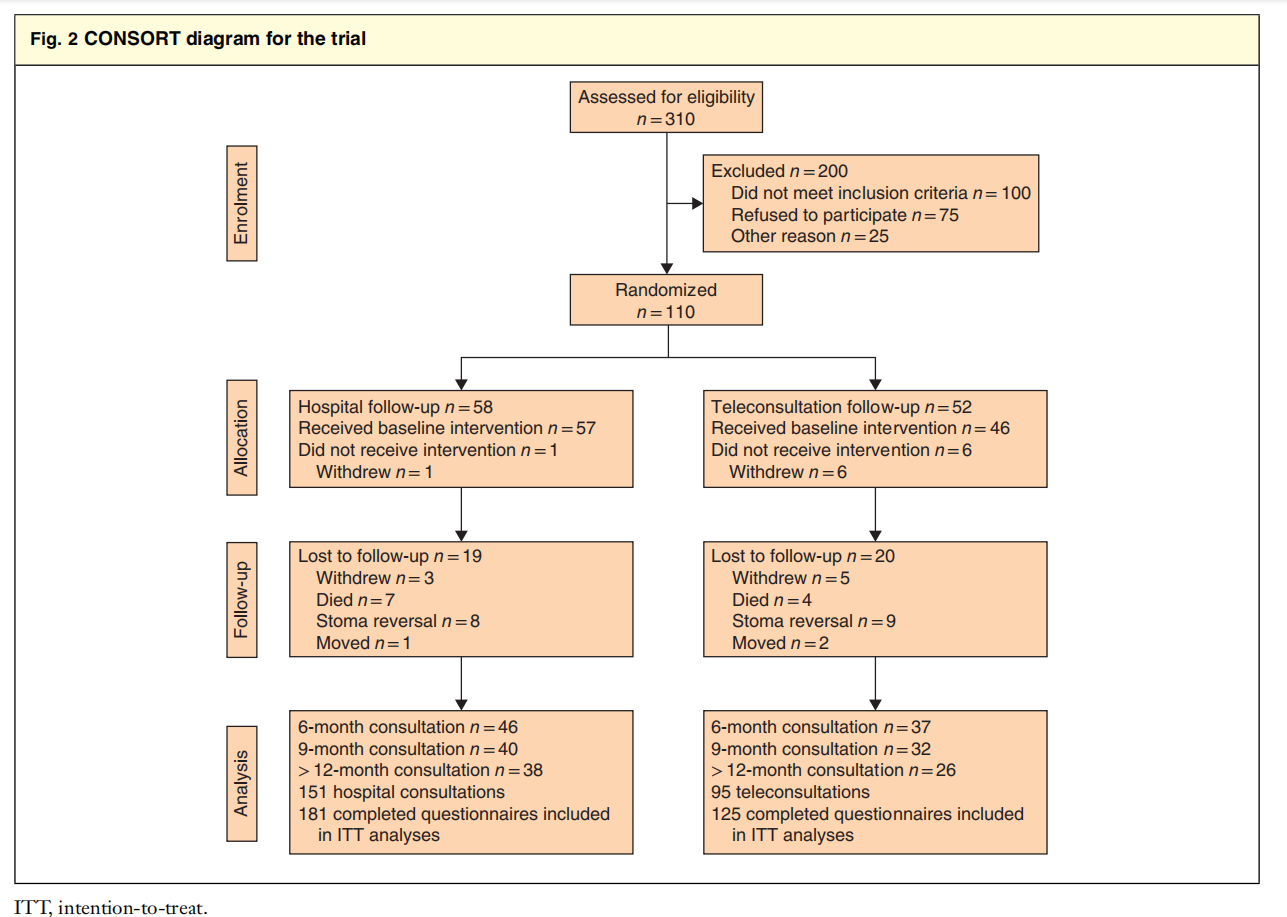

Statistical analysis

The intention-to-treat principle was used to analyse the data. The statistical analysis, including adjustment for co-variables, complied with the CONSORT statement15. Treatment arms were compared with respect to potential co-variables: continuous variables were compared with the independent samples t test and ANOVA, and categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test.

Responses to the five EQ-5D™ dimensions (for example1, 1, 2, 1, 3) were converted into utility (index) scores. Preferences (SPSS® syntax imputation) from a UK population were used, as no similar Norwegian preferences exist16. These calculated index scores were then used in the main analyses. The presence of any significant differences in QoL outcome measures (EQ-5D™ index and VAS scores) between baseline and 6, 9 and more than 12 months was determined. A general linear model was employed, and hospital versus intervention group were predictors in analyses of variance (between-groups ANOVA). EQ-5D™ index scores derived at baseline, 6, 9 and more than 12 months were compared in the model.

The OPEQ consists of ten rating scales based on factor analysis11,12. The questionnaire responses to ‘yes’, ‘no’ and ‘I don’t know’ were dichotomized, and compared with the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate.

For analysis of the Stoma Quality-of-Life Questionnaire, the scales (Work/Social Function, Sexuality/Body Image and Stoma Function) were scored according to the algorithm of Baxter and colleagues9. The scores for hospital and TC arms at baseline, 6, 9 and more than 12 months were then compared using between-groups ANOVA.

Missing data were treated as missing. Results for continuous outcomes were expressed as mean values with corresponding standard deviations, 95 per cent c.i. and associated P values. Two-sided P values are reported for all analyses; P< 0⋅050 was considered significant. Data were analysed with Excel® (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA) and IBM SPSS® version 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

One university hospital and five DMCs with designated TC studios participated in the study. The mean distance from the DMC to the university hospital was 375 km. The trial lasted until all enrolled patients had been followed for at least 12 months (from 2 February 2011 to 25 May 2016). Of 310 eligible patients with a stoma, 110 were included (58 in the hospital arm versus 52 in the TC arm) (Fig. 2).

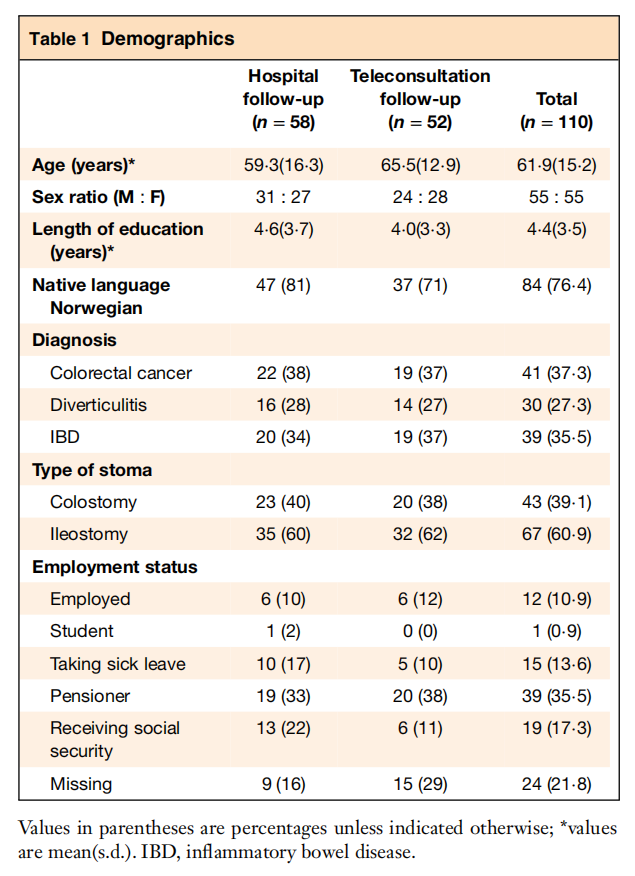

Twenty-three patients in the hospital group had an end colostomy compared with 20 in the TC group, and 35 and 32 patients respectively had an ileostomy. The trial generated 246 consultations (151 in the hospital arm and 95 in the TC arm), and 306 questionnaires were filled out (181 and 125 respectively). The mean age of patients in the hospital group was 59⋅3 years, compared with 65⋅5 years in the TC group, and 50⋅0 per cent of patients were men. Forty-one of the 110 patients (37⋅3 per cent) had surgery for colorectal cancer, 30 (27⋅3 per cent) for diverticulitis, and 39 (35⋅5 per cent) for inflammatory bowel disease (Table 1).

Eleven patients died during follow-up (7 in the hospital group versus 4 in the TC arm; P =0⋅534), and 17 patients had reversal of the stoma (8 versus 9 respectively; P =0⋅610). There were no identified adverse events in either group.

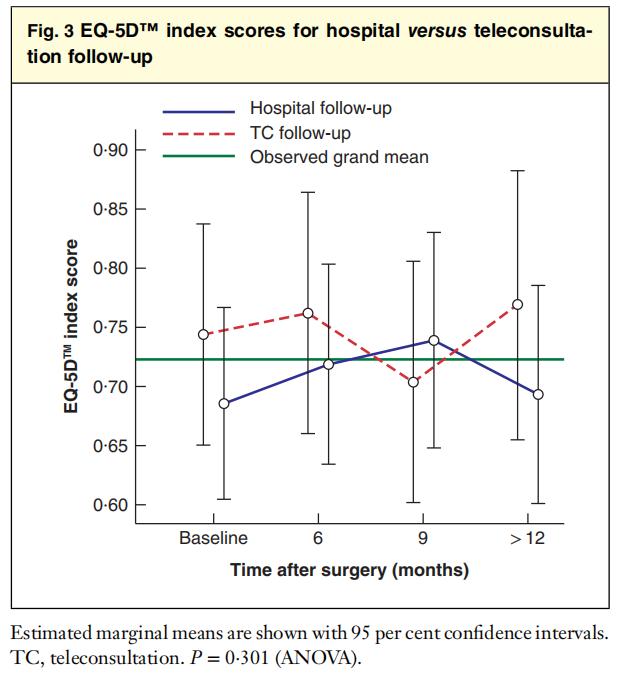

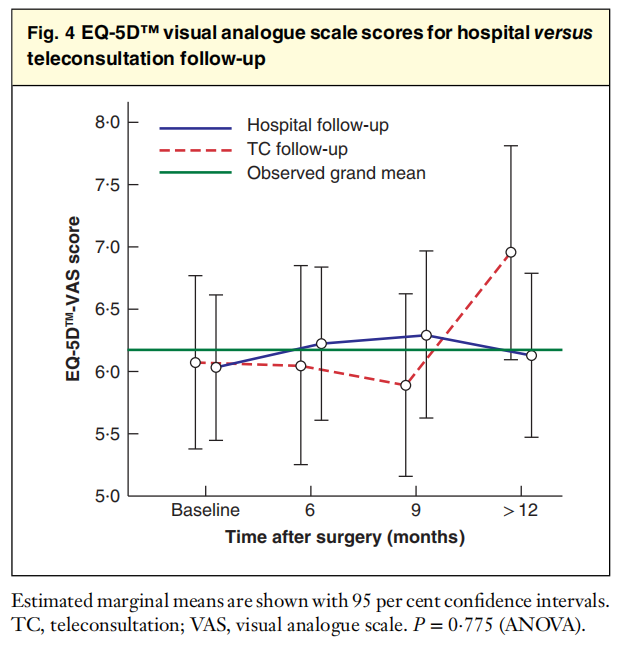

EQ-5D™ scores

There were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to the primary outcome, as determined by the EQ-5D™ index score (P =0⋅301) (Fig. 3). Similarly, there were no significant differences for the domains of Mobility (P =0⋅880), Self-care (P =0⋅825), Usual activities (P =0⋅647), Pain/discomfort (P =0⋅667) and Anxiety (P =0⋅272) (Table 2). EQ-5D™-VAS scores were also similar in the two groups (P =0⋅775) (Fig. 4).

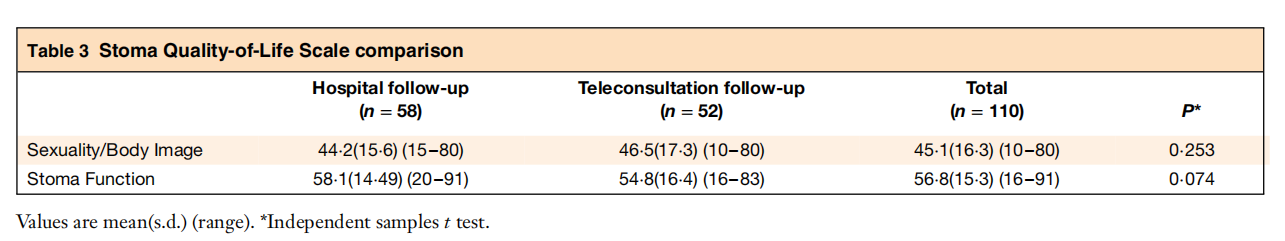

Stoma Quality-of-Life Scale

There were no significant differences on the designated Stoma Quality-of-Life Scale: Work/Social Function (P =0⋅822), Sexuality/Body Image (P =0⋅253) and Stoma Function (P =0⋅074) (Fig. 5 and Table 3).

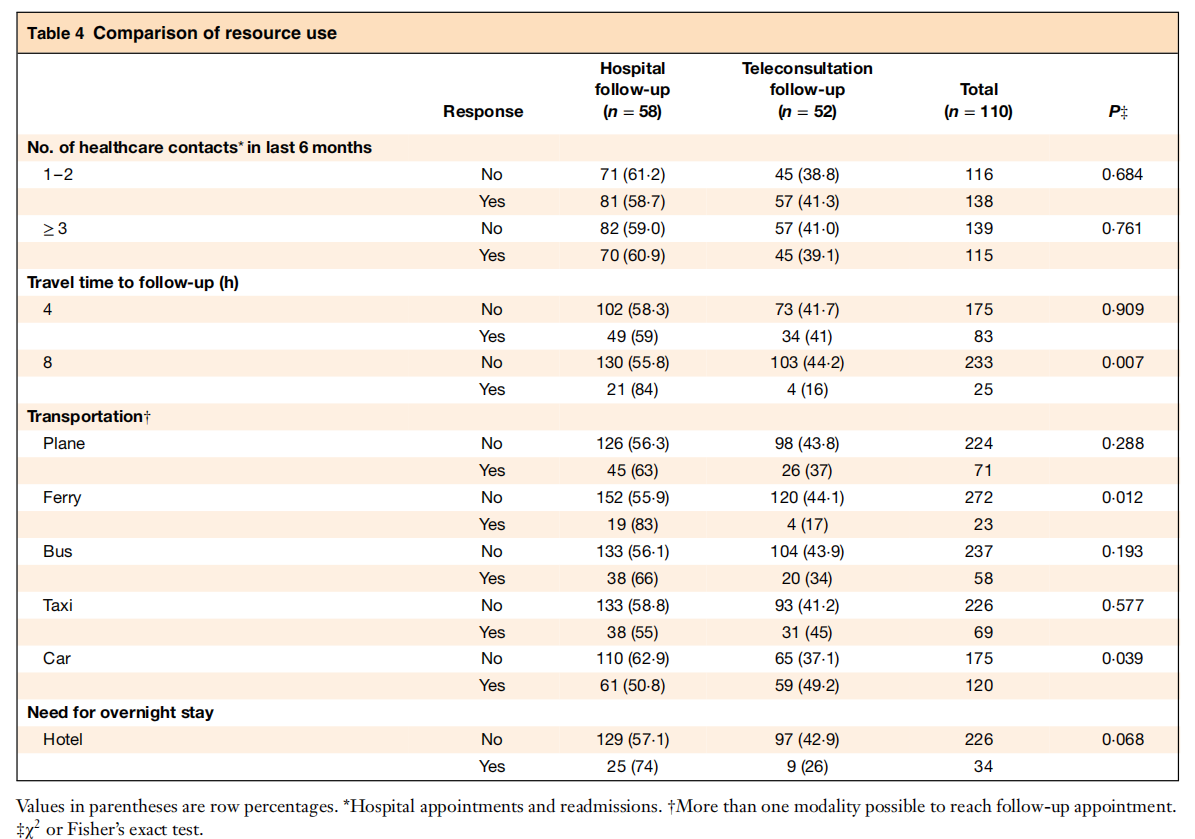

Resource use

There were no significant differences in the number of hospital appointment or readmissions (P =0⋅684). For mode of transportation, significantly more patients in the hospital group used car (P =0⋅039) and ferry (P= 0⋅012), and significantly more patients in the hospital group had a journey time of more than 8 h (P =0⋅007) (Table 4).

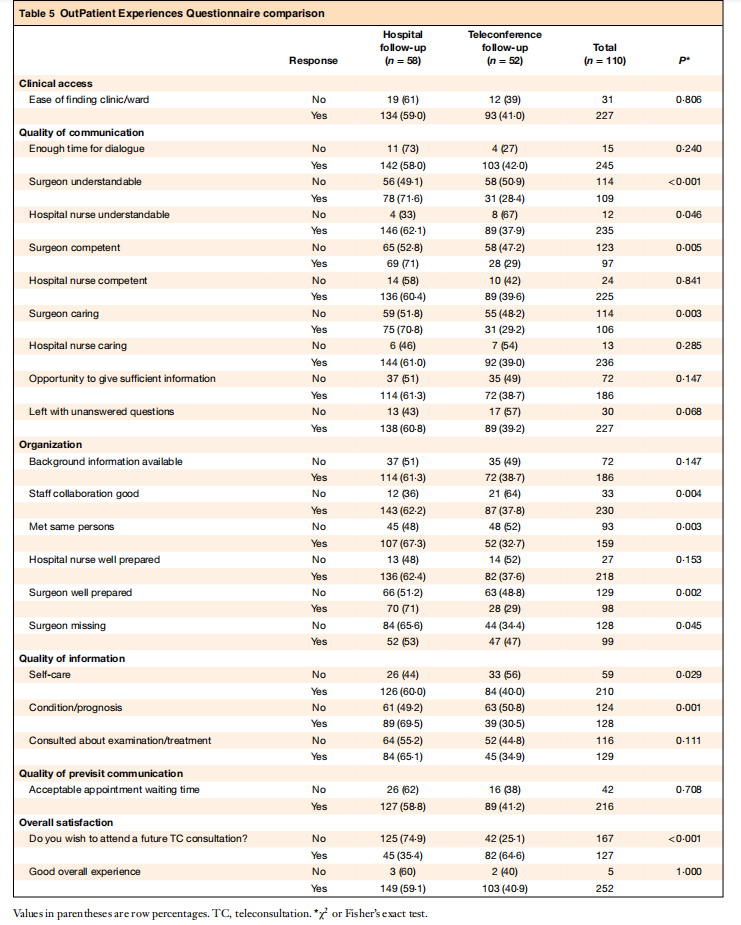

Outpatient experiences

The hospital group performed significantly better for items relating to organization of care (staff collaboration, P =0⋅004; met same persons, P =0⋅003) and communication (surgeon understandable, P <0⋅001; surgeon competent, P =0⋅005). Overall, there were no significant differences in the experience of hospital versus TC consultation (P =1⋅000), and most patients in the TC group chose TC over hospital follow-up as their next consultation option (P <0⋅001) (Table 5).

Discussion

TC follow-up did not generate more hospital consultations and decreased patients’ journey time significantly. There is, however, considerable room for improvement in TC organization and communication. Communication between healthcare providers participating in the TC arm showed a considerable quality gap, highlighting that communication during TC is challenging.

Internationally, TC is used as an instrument for follow-up of patients in the postoperative period and for outpatient consultation. Norway has experience with TC in haemodialysis, dermatology, orthopaedics and neurology17–19. Noteworthy is a recent randomized trial17,20 in which patients were examined by a district orthopaedic nurse under the supervision of an orthopaedic consultant located at the university hospital. There were no adverse events, and the TC service was cost-effective17,20. Nikolian and co-workers21 established an eClinic for patients undergoing cholecystectomy, appendicectomy or inguinal hernia repair. The eClinic was easily accessed by patients in the postoperative period, and led to an increase in QoL and reduced costs, compared with traditional outpatient follow-up appointments.

Wallace et al.22 compared joint TC between general practitioners, specialists (surgeons) and patients with the standard outpatient referral. They found that allocation of patients to virtual outreach consultations was associated with increased offers of follow-up appointments. However, it resulted in significantly increased patient satisfaction, and reduced tests and investigations. Efficient operation of such services will require appropriate selection of patients, considerable service reorganization, and the provision of logistical support.

TC can be used in almost any medical specialty, although best suited are those with a consultation that requires a high visual component. Stoma healing and wound management are thus prime candidates for TC follow-up. Development of suitable telemedicine systems in these fields could have a significant effect on wound care in the community, tertiary referral patterns and hospital admission rates4,23. TC in the surgical community has helped to deliver better care, especially in rural areas24.

During the 7 years of this study, video-conferencing technology has evolved to be more user-friendly. Technological difficulties may have impacted the results of the OPEQ study11. More dropouts were observed in the TC group (26 versus 20 patients in the control group), and some with drew from the study. Reasons for withdrawal were that patients felt they did not need follow-up (many were participating in parallel follow-up programmes after curative surgery for cancer)25. Finally, the Stoma Quality-of-Life Questionnaire has not been translated into Norwegian, and the trial group did the translation. This may have impacted interpretation of the questions and be a potential source of bias. The strength of the study is the randomized study design, providing high-quality data on a scientific topic with limited evidence.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Northern Norway Health Care Trust (Helse-Nord), which funded the STOMPA trial (4031/HST951-10). The authors express their sincere gratitude to K. V. Kleiven and Å. I. Erikstad for data-gathering and organization of the video consultations. I. Sperstad at the Clinical Research Centre was in charge of data-handling, a job she carried out with great professionalism. Finally, the authors thank the stoma nurses located at the DMCs. This trial would not have been possible without their commitment.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1 Eadie LH, Seifalian AM, Davidson BR. Telemedicine in surgery. Br J Surg 2003; 90: 647–658.

2 Augestad KM, Lindsetmo RO. Overcoming distance: video-conferencing as a clinical and educational tool among surgeons. World J Surg 2009; 33: 1356–1365.

3 Lacy AM, Bravo R, Otero-Piñeiro AM, Pena R, De Lacy FB, Menchaca R et al. 5G-assisted telementored surgery. Br J Surg 2019; 106: 1576–1579.

4 Huang EY, Knight S, Guetter CR, Davis CH, Moller M, Slama E et al. Telemedicine and telementoring in the surgical specialties: a narrative review. Am J Surg 2019; 218: 760–766.

5 Panesar SS, Ashkan K. Surgery in space. Br J Surg 2018;105: 1234–1243.

6 Doarn CR. The power of video conferencing in surgical practice and education. World J Surg 2009; 33: 1366–1367.

7 Augestad KM, Han H, Paige J, Ponsky T, Schlachta CM, Dunkin B et al. Educational implications for surgical telementoring: a current review with recommendations for future practice, policy, and research. Surg Endosc 2017; 31: 3836–3846.

8 Ellimoottil C, Boxer RJ. Bringing surgical care to the home through video visits. JAMA Surg 2018; 153: 177.

9 Baxter NN, Novotny PJ, Jacobson T, Maidl LJ, Sloan J, Young-Fadok TM. A stoma quality of life scale. Dis Colon Rectum 2006; 49: 205–212.

10 Rabin R, Oemar M, Oppe M. EQ-5D-3L User Guide: Basic Information on How to Use the EQ-5D-3L Instrument. EuroQol Group: Rotterdam: EuroQol Group, 2011.

11 Garratt AM, Bjaertnes ØA, Krogstad U, Gulbrandsen P. The OutPatient Experiences Questionnaire (OPEQ): data quality, reliability, and validity in patients attending 52 Norwegian hospitals.Qual Saf Health Care 2005; 14: 433–437.

12 Pettersen KI, Veenstra M, Guldvog B, Kolstad A. The Patient Experiences Questionnaire: development, validity and reliability. Int J Qual Health Care 2004; 16: 453–463.

13 Campbell MJ, Julious SA, Altman DG. Estimating sample sizes for binary, ordered categorical, and continuous outcomes in two group comparisons. BMJ 1995; 311: 1145–1148.

14 Roset M, Badia X, Mayo NE. Sample size calculations in studies using the EuroQol 5D. Qual Life Res 1999; 8: 539–549.

15 Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010; 340: c869.

16 Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, Williams A. The time trade-off method: results from a general population study. Health Econ 1996; 5: 141–154.

17 Buvik A, Bugge E, Knutsen G, Småbrekke A, Wilsgaard T. Patient satisfaction with remote orthopaedic consultation by using telemedicine: a randomised controlled trial. J Telemed Telecare 2018; 21: 1–9.

18 Müller KI, Alstadhaug KB, Bekkelund SI. A randomized trial of telemedicine efficacy and safety for nonacute headaches. Neurology 2017; 89: 153–162.

19 Norum J, Pedersen S, Størmer J, Rumpsfeld M, Stormo A, Jamissen N et al. Prioritisation of telemedicine services for large scale implementation in Norway. J Telemed Telecare 2007; 13: 185–192.

20 Buvik A, Bergmo TS, Bugge E, Smaabrekke A, Wilsgaard T, Olsen JA. Cost-effectiveness of telemedicine in remote orthopedic consultations: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2019; 21: e11330.

21 Nikolian VC, Williams AM, Jacobs BN, Kemp MT, Wilson JK, Mulholland MW et al. Pilot study to evaluate the safety, feasibility, and financial implications of a postoperative telemedicine program. Ann Surg 2018; 268: 700–707.

22 Wallace P, Haines A, Harrison R, Barber J, Thompson S, Jacklin P et al.; Virtual Outreach Project Group. Joint teleconsultations (virtual outreach) versus standard outpatient appointments for patients referred by their general practitioner for a specialist opinion: a randomised trial. Lancet 2002; 359: 1961–1968.

23 Sun V, Ercolano E, McCorkle R, Grant M, Wendel CS, Tallman NJ et al. Ostomy telehealth for cancer survivors: design of the ostomy self-management training (OSMT) randomized trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2018; 64: 167–172.

24 Hwa K, Wren SM. Telehealth follow-up in lieu of postoperative clinic visit for ambulatory surgery. JAMA Surg 2013; 148: 823–827.

25 Augestad KM, Norum J, Dehof S, Aspevik R, Ringberg U, Nestvold T et al. Cost-effectiveness and quality of life in surgeon versus general practitioner-organised colon cancer surveillance: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2013; 3: e002391.

© 2020 University Hospital North Norway and University of Tromsø. BJS published by JohnWiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of BJS Society Ltd.BJS 2020; 107: 509–518

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.