文献精选

This article is excerpted from the 《Frontiers in Plant Science》 by Wound World

This article is excerpted from the《Frontiers in Psychology》 by Wound World

This article is excerpted from the 《Frontiers in Medicine》 by Wound World

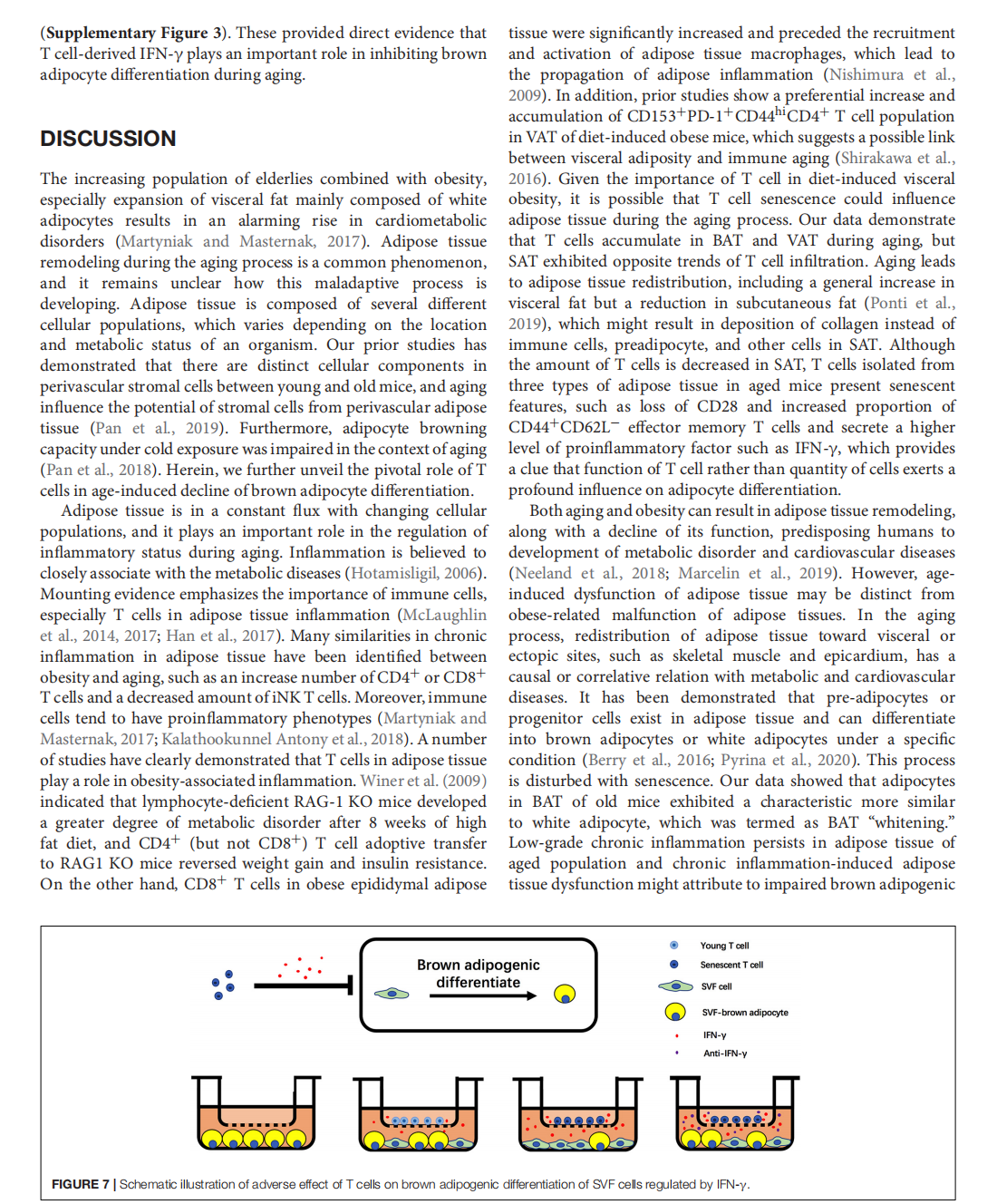

This article is excerpted from the《Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology》 by Wound World